EPISODE 45

April 6, 2023

Introduction

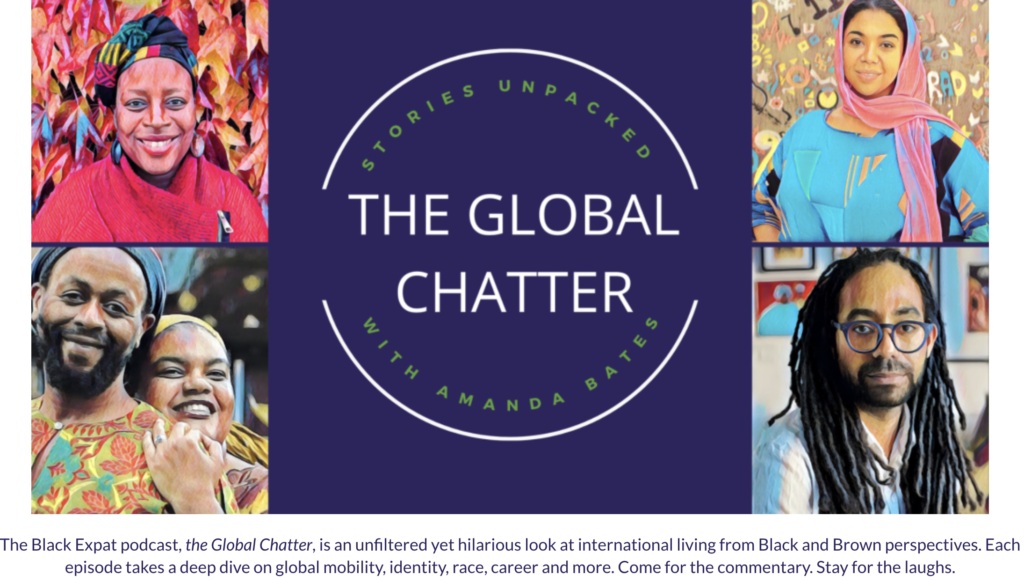

Founder of The Black Expat and The Global Chatter Podcast, American Amanda Bates, talks about her cross-cultural experiences growing up in an immigrant community in the US and moving in her tweens to her parent’s West African passport country, Cameroon. She explains how and why as an adult she was in the perfect position to change perceptions of black and brown global mobility, especially for folks of color who historically, have not been afforded the opportunity to see themselves represented as expatriates.

TRANSCRIPT

[00:00:00] Louise: Welcome to Women Who WaIk. I’m Louise Ross, writer and author of Women Who Walk the book, the inspiration for this podcast. And just as I did for the book here, I’ll be interviewing and unpacking the journeys of impressive, intrepid women who’ve made multiple international moves for work, for adventure, for love, for freedom – reminding us that women can do extraordinary things. You can find a transcript, with pictures, to each episode, and my books on my website, LouiseRoss.com.

[00:00:48] Louise: Hello, listeners. Welcome to Episode 45 of Women Who Walk.

[00:00:53] Louise: My guest today is Amanda Bates. Amanda currently lives in North Carolina in the US. She was born in the 1980s to West African parents in Washington, DC where she grew up in a diverse immigrant neighborhood.

[00:01:10] Louise: When Amanda was 10, her parents repatriated to Cameroon, their country of origin, and where Amanda spent the next seven years straddling the cultures of Cameroon and the International American school she attended. As a result of her cross-cultural experiences, she identifies as an Adult Third Culture Kid, a topic I cover in-depth in Episode 30.

[00:01:39] Louise: I was first introduced to Amanda when she was the keynote speaker for Families in Global Transition 2021 online conference. I’ve mentioned FIGT.org in previous episodes, but in case you are new to the podcast in short, Families in Global Transition is a welcoming forum for globally mobile individuals, families, and those working with them.

[00:02:09] Louise: Unfortunately, I missed that presentation of Amanda’s. However, knowing that she’s a sought after speaker on the Black experience abroad, I listened to several podcast interviews that she’s given, at which point I knew I wanted to talk with her, because The Black Expat, which is also the name of her website, is a topic that is too often overlooked when discussing expatriation or people living outside their country of origin.

[00:02:41] Louise: As Amanda points out during our conversation, the term expat has historically not been afforded to folks who are black and brown. Instead, we are more likely to think migrant or refugee. And living in Portugal where there’s a significant population of people of color, individuals, couples, families from Africa, Brazil, India, it’s simply misguided to reason that all these people are migrants or refugees.

[00:03:12] Louise: In the following discussion, Amanda animatedly explains why it has become her mission to change perceptions of black and brown global mobility, especially for the black and brown community who again, have not been afforded the opportunity to see themselves represented as expatriates.

[00:03:33] Louise: This is a fascinating and important discussion, and there’s no one better suited to leading the conversation than my guest, Amanda Bates, who also has a talent for infusing her interviews with levity and laughter?

[00:03:59] Louise: Thanks Amanda for being a guest on Women Who Walk. Now you are, uh, in Washington, DC where you were born to Cameroonian parents who had immigrated to the US in the mid- seventies. Had they immigrated to further their education or were they young professionals seeking work opportunities?

[00:04:18] Amanda: First, I just wanna say thank you for having me on your show. I think this is such a great platform, with these stories. Yes, I was born in DC I actually don’t live there now, although I go back quite a bit cuz I have family that’s in the area. And my parents were a part of what I say of the great African migration or the start of it in, in the seventies and eighties, where they had the opportunity to leave their country of Cameroon, they are Anglophone speaking, to come to the US. My mom had an opportunity, and she was married at the time and so my dad came with her, and they were coming to find and I guess seek opportunities, which is what the main reason most of us move, and to also further education.

[00:05:03] Amanda: They ended up living and moving in an area of immigrants, particularly from West Africa, which was where they were from, as well as Central America. And so it was a pretty vibrant time, I think with their move.

[00:05:18] Louise: Mm-hmm. I just picked up on one thing that’s, uh, which I’d rather love, which is that in effect your dad followed your mom, that she had the opportunity.

[00:05:27] Amanda: Yeah, yeah. Yeah. We don’t talk about that enough, I think, in expat spaces where a male partner will follow, so yeah.

[00:05:35] Louise: Yeah. So growing up in DC in the eighties with West African parents, what was your early childhood like?

[00:05:42] Amanda: Yeah. What was it like? It was loud. But I think that’s mostly because we were Cameroonians. You know what, yes, I always say I was this American kid, definitely outside the doors of our home, but within the home it was very, very Cameroonian influenced. Obviously my parents being immigrants, and I think this is the story of anybody, immigrant, expat, whatever the terms being used, is that you first try to find the people who are the closest to your origin story. So like connections with the people that you know from home.

[00:06:18] Amanda: And then I think the next level are okay, maybe not those people, but people who have similar experiences. And so I would say growing up it was both, right? It was growing up in a Cameroonian home with a lot of, I’m gonna say extended family, extended friends, whatnot. Food, the food was a big part. My parents made Cameroonian food. I didn’t really eat a whole lot of American food, which I think to this day is why I’m not really fond of sandwiches, cause we just didn’t grow up eating sandwiches and I never really took a sandwich for lunch.

[00:06:49] Amanda: But also because of where they were and this time where it wasn’t just West Africans and East Africans moving, but Central Americans, there was an extended, international immigrant community beyond those doors. So people who were from El Salvador and Guatemala and countries that were in turmoil at that time.

[00:07:10] Amanda: When I look back at that period, I also have to remember my parents were learning the culture as they were raising kids.

[00:07:16] Louise: Mm-hmm.

[00:07:17] Amanda: And so I would say my childhood was very hybrid because I’m the first one in my family that was born in the United States. Everybody else had a history and a memory that came from somewhere else. I think even some of the cultural norms my parents didn’t know because they just didn’t grow up in them. It’s funny as an adult now, because there are things that I do that is such a hybrid as a two , so, yeah.

[00:07:41] Louise: Understandably. Well, um, I have to ask you, what did you take to school for lunch if it wasn’t sandwiches?

[00:07:48] Amanda: Oh my gosh. My mother. So here’s the thing I would say, and I actually don’t think this is particular to Cameroonian mothers or West African mothers, I think it’s just what people do. The tendency is to take whatever version that was made at home and just put it in child portions and take it with you. Right. And I think

[00:08:12] Louise: Leftovers. Leftovers.

[00:08:13] Amanda: Yeah. Yeah. And I think about like, friends that I knew who were from Asian cultures, who were like, yeah, we would take our little bento boxes cuz it makes sense, right?

[00:08:21] Amanda: My, my family, I mean, being West Africa, there’s everything from like fried plantains and jollof rice, which people know, to, there’s an okra soup, which would be similar to gumbo in the US and it was just literally whatever, like child-size version of whatever was cooked in the house.

[00:08:39] Louise: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

[00:08:40] Amanda: Sometimes I think it may have smelt different than what everybody else was eating, which always draws attraction, but my mother was not gonna go out of her way to make something that she does not normally make.

[00:08:54] Louise: Yeah, and it sounds a lot healthier than sandwiches.

[00:08:57] Amanda: Oh, for sure, for sure.

[00:08:59] Louise: So when you were 10, the family repatriated to Cameroon and the Francophone capital of Yaoundé.

[00:09:07] Amanda: Yaoundé, you got it!

[00:09:10] Louise: And, uh, but your parents were from the English speaking minority. Talk us through the adjustments that your parents were making repatriating, because this is such a big issue, having lived outside of their country of origin and for, for anyone repatriating, and the cultural adjustments that you were making, because I guess at this point, having spent your childhood in the US you felt very much like an American.

[00:09:33] Amanda: Yes. So I, up until that point, had only been to Cameroon once and I was two. I hadn’t lived in the country. I hadn’t spent extensive time in the country, I think it was to visit extended family, particularly grandparents. And that was it. My parents, when they moved or made the decision to move, initially were thinking about the English speaking part, and I think it’s because obviously that’s where their cultural ties and family were. But the reality is, like anywhere else, the capitals of a country are usually the economic center and the capital was, of course, Francophone.

[00:10:07] Amanda: I think if I look back for my parents, it was a big adjustment because at that point they had been out of the country, as far as living, at least 10, 11 years. So it’d been at least a decade, and I think anyone who knows, it doesn’t matter where you go, it could go to the town over or the country over or across the world, once you’ve been out of a place you think you know and remember how things function, and then you’re like, oh yeah, I blocked that outta my mind, or, oh, this has changed.

[00:10:37] Amanda: That was part of the drive where we ended up living in the Francophone part was just because there were more opportunities where things weren’t as much or, let me put it this way, where they were before, you were just kind of removed from that economy and that economic opportunity.

[00:10:54] Amanda: I think it was an adjustment for them in the sense that people who know you before, and this is anybody, right, they remember you from before, and you might look the same, but they don’t necessarily understand, oh, but you’ve had all these other experiences and so maybe your worldview has changed. And so I think that there was adjustment for that for them.

[00:11:12] Amanda: For me, on the other hand, it wasn’t even a repatriation, it was an expatriation because I’d never lived there. I’d never lived in either part of the country, and I did not understand a lot of the, the morays and the, and the cultural context. I thought I did, and keep in mind I was 10 when I moved. I probably thought, okay, my parents come from this place, there’s stuff that I know because of that. But then you realize, well, the version I was getting was like a hyphenated version. Because they were out of their culture imparting some of their culture, but in a new environment and context. Now, being back in the original culture, I wasn’t seen as Cameroon American or African American, whatever term you wanna use, they were just like, you’re American. Like straight up.

[00:12:05] Louise: Yep.

[00:12:05] Amanda: And I, and, and, and you know, the funny part is as an adult now, especially as I talk and coach people through expatriation, obviously my focus is in the Black Expat world, for some people it’s a shock, especially when they go to predominantly black countries where all of a sudden, where they’ve been African American or black Canadian, or Afro French, and now it’s like, no, you’re just the second half of that, and it’s like, wait, what? Like, that’s not even an option completely in my, in my passport country.

[00:12:33] Amanda: And so the first adjustment, and this is speaking as a kid, was incredibly hard. It was incredibly hard. I think most people can relate to that, irrespective of age. But for me, between a language barrier, a cultural barrier, I was entering my pre-teens, honestly, going from a western country to a non-Western country I think is very tricky for kids, especially when they’re entering their pre-teens and in teens, in particular.

[00:13:02] Amanda: Honestly I think it’s the same, going from, not the same, but in a different way, struggle, going from a non-Western to a western country. As I’ve gotten older and I saw my own childhood, and I’ve talked to teens who moved at like 13, 14, and it’s like, here you are, you left Britain, now you’re in Tanzania, uh.

[00:13:22] Louise: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

[00:13:23] Amanda: It’s a shift. And so it was hard. But I eventually got my footing cuz I eventually got to the international school and I ended up going to two international schools and that was really good for me.

[00:13:34] Louise: Yeah. Yeah. I listened to, uh, an interview you did with someone, and I vaguely recollect that, that you had also been homeschooled for a period. Is that because there were so many challenges at school for you and, and your parents decided to just keep you at home and school you there so that you could slowly make adjustments?

[00:13:55] Amanda: I wish it was that. What it was is that they , they decided to move in the middle of the academic year. I think we left January, February of the year I turned maybe 10 or so. It was the middle of school year and they were just like, well. In the States, I was ahead academically, so I think they were just like, well, we’ll just homeschool her. I wish this was really formalized. It really wasn’t. I guess we would call it kind of homeschooling, right, these days. And so, yeah, that was what it was. Then they put me in a local boarding school, which was a disaster.

[00:14:26] Louise: Were you actually boarding or were you a day? Oh, I was day kid. You were okay.

[00:14:31] Amanda: It was terrible for me. The school was fine, it’s one of the better schools in the country, in that region. But for me the adjustment, like I was sick, like physically, physically getting ill. And then they decided let’s put her in the international school. I was at the American school until ninth grade and then they did not have a high school at that time. And I went to another international school in the city and that’s where I graduated from.

[00:14:56] Louise: Okay. Well that makes sense in terms of my next question because you returned to the US for university and

[00:15:03] Amanda: mm-hmm

[00:15:04] Louise: when I read this about you, I thought, well, why the US? But if you had been at an international American school, was that the reason?

[00:15:13] Amanda: Yeah. I mean my parents both hold American degrees. My mom, both her undergrad and Masters and my dad undergrad for sure, and actually Masters. I think there was never a question and I think for two reasons. One, because they already had a history of having been through advanced US education. But I think the other part is cause I was a US passport holder, seen as a golden ticket in that part of the world, and why wouldn’t I? My mom was also working, she was a local hire, but was also working at the US Embassy. So I was in that world and I think there was never an assumption by anybody, even outside my parents, that I would go anywhere else.

[00:15:56] Louise: What was it like stepping out of the predominantly African community of Cameroon and into the predominantly white college campus or onto a, a white college campus? Hmm. And from an international school to an all-American college, did you feel culturally confused or culturally misunderstood by your peers?

[00:16:15] Amanda: Let me start with this. When I was in high school, I think like all high school students you think you know a lot more than you do. So when I was applying to universities, I was looking for the biggest, baddest American experience possible, because at that time, this is gonna date me, but some of y’all will know this show, 90210, was really big and we were, we were kind of obsessed, and I was like, you know what? I want that experience.

[00:16:44] Amanda: We’re in our small international school. We went the football games and all the stuff, right? The cheerleaders. We want that experience. I applied to multiple universities and I had maybe one college on my list that was small, like really small. They accepted me and I’m like, I’m not going because I’m coming from a small high school. Really small, even by international school standards. And I was like, it’s just gonna be like high school.

[00:17:10] Amanda: Now, here’s the thing, in my infinite wisdom, as a 16-year-old, 17-year-old, the college was still bigger than my high school, so it was not gonna be like high school. I instead went to the largest state public institution in North Carolina, which at that time was definitely pushing past 20,000. And in my mind I was like, I’m gonna have the biggest American experience. Oh my gosh. Can I tell you?

[00:17:39] Louise: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

[00:17:40] Amanda: It was really rough, for multiple reasons. One, and I’ve said this a lot in Third Culture Kid talks, when you go to a school like that, most of those people are from the state. And most of them may go home over the weekends. And most of them came to college with friends from high school. And so they already had networks even as first years that I did not have. Cause there was nobody I went to high school with who was coming here. The second part, I didn’t realize how easy it was to get lost in the sauce, like because it was so big, and so the experiences that I thought I was gonna have, I did not have at all, because the adjustment was really hard.

[00:18:25] Amanda: At that time, for orientation, if you were tagged as an American student, you couldn’t go to the international student orientation. It wasn’t an option. They figured you’re American, you know the country, you’re fine. Instead of understanding if you’re an American kid who grew up abroad, yeah, you sound American and you know some things and maybe you come here for a holiday. But if you spent most of your formative years somewhere else you’re not fully American in the way that people think you are.

[00:18:56] Louise: So wait, wait, wait, wait. So you, you weren’t allowed to go to the international orientation because …

[00:19:01] Amanda: It was not an option at that time. It was only for international passport holders. Wasn’t only our school. There were a lot of schools at that period who did that. What thankfully has changed is that a lot of schools have recognized that you have these students who, even if they are nationals of the country, who’ve had these international experiences and they’ve made it easier or they have the option, or they’ve even created maybe a Third Culture Kid option as well.

[00:19:29] Amanda: But, this was pretty common in the nineties, like if you talked to my friends I went to high school with, none of us really could go to the international option. Truly not an option. And it’s unfortunate because there’s so many things I think that happened in that orientation that we could have benefited from.

[00:19:43] Louise: Oh, absolutely.

[00:19:43] Amanda: Well, yeah, I mean, once again, I think people are, Okay, you are tagged as an American and then maybe you got in-state residency because your family was from Florida and because they paid taxes there, even though they may have a house there but haven’t lived there in 15 years or whatever. But it does not mean you’re like the other students that are coming in. And so the adjustment, I will say was very rough, at least for the first two-and-a-half-years, until I got connected to the African Student Union and then there, I found peers who were first generation Americans, or they had lived in the origin country for a bit or they just had some kind of international story and also we had some cultural similarities, and that’s when I started to thrive.

[00:20:30] Louise: Yeah, makes absolute sense. And so you’re talking about being a Third Culture Kid, and I just want to alert listeners, if you want to dig a little deeper on Third Culture Kids, Episode 30 is all about Third Culture Kids. And so with these experiences that, um, you had both home and abroad, it’s as though you were really primed to make these experiences work for you. Or rather, you’ve made a career out of your expertise in cross-cultural living, which you’ve, you’ve kind of alluded to. So tell us about that.

[00:21:01] Amanda: Yeah, so I started The Black Expat, back in, well it launched live in 2016. I started it really in 2015, and it was two reasons. One, I was at the time preparing for a move. I was moving to the Middle East. Prior to my move, I had been working in a nonprofit that served underrepresented high school students that were preparing to transition out of high school. Either they were going to college or they’re gonna go to a trade program. And one of the things I would always wanna encourage them to do was to study abroad.

A friend of Amanda’s in Lisbon, Portugal. The image is featured on her website TheBlackExpat.com

[00:21:36] Amanda: Because I’d had this international background and I thought it was transformative and it would do them well, especially coming from underrepresented backgrounds. Every single time, and mostly students were black and brown, they would say, Miss Amanda, I don’t know anyone who lives abroad who looks us, with the exception of the military. I just felt like that can’t be true. I know plenty of black and brown people who live abroad. I’m going to ask the experts in cross-cultural work, trainers and specialists. And I’m gonna ask the black folks who I know our name in this space and what they see. And, and every single one of them said, no, there really isn’t a platform that talks specific to the black experience.

[00:22:15] Amanda: And I thought to myself, okay, I’m just here to normalize. I really didn’t have any grand plans. Look, I’m a third culture kid. I know a ton of people, who moved for business or government or missions or whatever, I’m just gonna create a site, um, because I’m Type A like that and then I’m gonna move to Doha.

[00:22:32] Amanda: That was the first reason. But then the second reason was that I was thinking about like my mom’s generation, and the black expats who had moved in the fifties and the sixties and the seventies and even before that, and how, this is not a new concept, but we never really documented that this was happening.

[00:22:51] Louise: Hmm.

[00:22:52] Amanda: And so I kept thinking, well, there are generations of black people who have moved, separate from often what you hear is trauma. For example, in the US, a lot of times when you hear about black migration, it starts with a transatlantic slave trade.

[00:23:07] Louise: Mm-hmm.

[00:23:07] Amanda: People moving because of persecution, racism, whatnot, which is fair and which is valid and which is noted, and I don’t shy away from, but then I’m also like, yeah, there are also people who moved in the fifties cuz they just really want to live in Benin. And that should be part of the story too, because other groups get to have expat stories that don’t necessarily start with trauma. Not every black expat story has to be rooted in trauma. It could just be somebody fell in love.

[00:23:35] Louise: Or, it can be just choice. Personal choice.

[00:23:38] Louise: Right.

[00:23:38] Louise: To move country.

[00:23:39] Amanda: Right, right. But here’s the thing, it makes sense to you and I, but then thus again, I get asked to speak a lot cuz it’s still weird to people. It’s logical when you walk through it, right? It’s like people move. That’s what I say all the time. Why Black Expat? Cuz people move.

[00:23:56] Amanda: Actually, this was the first time where I said this is inclusively black, so wherever you come from, and that includes multiracial, biracial, and adoptees, and so this was the first time, I think someone actually just said, we’re gonna create a platform around this. And it was a response to not only is this something that’s happening now, but I wanna make sure that people understand it’s something that’s always been happening.

[00:24:20] Amanda: And there are stories that we wanna document because we’re not all gonna be here forever. And I, I think there’s some beautiful stories that, that are worth hearing. And so I launched it in 2016 with no expectation and it turned into, oh my gosh, I need to also give people advice because they wanna go abroad for the first time and then it also turned into a lot of social justice conversations, I think particularly after George Floyd in 2020.

[00:24:47] Louise: Mm-hmm.

[00:24:48] Amanda: And then it also turned into, oh, I think you need to hear these people live. And so the Global Chatter podcast was born as well.

[00:24:56] Louise: Ah, yes. Well, we’ll get there. Um, one of the things I noticed on your website, The Black Expat, mm-hmm, is that there’s a dropdown where you give the definition of an expat. When I saw this, I thought, that’s interesting, I wonder if Amanda had included this because people of color, perhaps when they read it, they can say, ‘oh, that’s me. That’s me. Or that was me, or that was my parents.’ Am I right or was there a different reason for you giving an explanation of what an expat is?

[00:25:29] Amanda: Oh, totally. You hit on it. So this is just the truth of the matter. Oftentimes when you see black people in migration, the term immigrant is used, refugee is used. The word expat historically has not been afforded to folks who are black and brown. The other thing, and let me tell you, and this goes into a story about the name. The name is super simple, it’s called The Black Expat. The reason I called it The Black Expat is that I just wanted black folks to find it. Simple.

[00:25:56] Amanda: I kept getting into interviews where people told me, wow, this is a really political name. And I’m like, really? I was like, I think I know where you’re going, but tell me more. And so for the non-Westerners, they would say to me, and they said specifically non-Western black individuals. I, I remember conversations where folks said, oh, is this for Americans and Europeans? And I was like, why? And he was like, because we never get to be called expats as Africans. I was like, Yeah, I know. That’s why it’s called The Black Expat. Right?

[00:26:29] Amanda: And then the question around, well, why’d you use the word black? Especially in countries where we’re predominantly black, we don’t necessarily identify ourselves as black. I’m like, I know, but if I don’t use the word black, y’all are not gonna know where to find it. So the reason I have that primer on expatriation is because, when groups have historically not been called those things, including Third Culture Kids, I wanna give everyone a baseline. And I also want to give people the opportunity to understand that they are a part of this because expat has a classist notion to it. And if it’s really around movement, why you move? Sure. We can debate, you know that, and I think that’s what the big debate is. But if it’s around just movement, then a lot of people technically are expats.

[00:27:21] Amanda: I think about a year ago I was like, let me actually define this thing and in many categories, as you could see.

[00:27:26] Louise: Mm-hmm,

[00:27:27] Amanda: I think somebody retweeted it and they’re like, oh my gosh. I was like, they’re a couple I haven’t even thrown up there that I’m still thinking to myself, I need to add these two, just so I, I think I’ve got everybody covered. But yeah, that’s where the, that’s where that post was created or why it was created.

[00:27:42] Louise: And you know, the, the term, not that it’s evolving, but I think the, the experience is evolving.

[00:27:48] Amanda: Mm-hmm.

[00:27:49] Louise: I mean, I moved to Portugal independently and I’m one of many who have moved to Portugal independently. Single women of all color, from many, many countries around the world who have moved here just because they can. Which is a unique period in history, where women are resourced to the extent that they can make decisions

[00:28:09] Amanda: mm-hmm.

[00:28:09] Louise: about moving country, without following a partner, without being relocated with their partner’s company. Perhaps some of these women have been relocated with their work, with their company and their husband follows them. I think of myself more of a, an immigrant because I have moved countries intentionally to have a new experience and to immerse myself in that country and to stay there for a period. And I don’t feel like an expat for that reason. So I see this term sort of evolving as people cross borders by choice.

[00:28:43] Amanda: Mm-hmm.

[00:28:44] Louise: How do you feel about that?

[00:28:46] Amanda: I think you’re right. I was having this conversation with a long time expat, if you will, someone that I’ve known since I started this, and she’s black, she was a single mom. She’s now married, again and has had several moves. And I’m pretty sure this is her last move. Like she’s made a ton of moves. I was asking her and I was like, at some point I think you stopped being an expat. Yeah, she’s American, but she’s married to this man who’s from this country, of the soil, as I like to say.

[00:29:16] Amanda: I think if you talk to folks who have moved somewhere and been somewhere for a while, they stop seeing themselves as an expat, and I get it, and I don’t actually disagree with it because at some point you’re building roots in a country. I think in the next five-to-seven years this term will I mean, it already looks wholly different than when I was a kid. So I think it’s gonna be, especially when we add this concept of digital nomads, right?

[00:29:44] Louise: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

[00:29:45] Amanda: It’s just gonna keep changing and I’m okay with it. And I actually still feel like, okay, that means maybe we can get back to the original definition. Really, it’s just movement.

[00:29:55] Louise: Mm-hmm.

[00:29:56] Amanda: If you just keep it to movement. Right? And don’t even necessarily put a time limit on it, then I’m like, yeah. Okay. Somebody exited one location and they went to another. And take the politics and the class out of it.

[00:30:07] Louise: I love that.

[00:30:08] Amanda: Yeah.

[00:30:08] Louise: Yeah. So let’s go to the Global Chatter podcast. Tell us about that.

[00:30:14] Amanda: Sure. Like all good things came outta 2020. Covid.

[00:30:17] Louise: So did this podcast. Yep.

[00:30:19] Amanda: Right. Um, and so long story short, the storytelling on the website, I was already doing audio interviews, we were just transcribing them. And the thing is, is that as the site has evolved and the platform has evolved, so has audience preferences evolved and I wanted to give people the opportunity to hear and listen to the inflection in people’s voices and the excitement and the drama of, of their story.

[00:30:46] Amanda: And honestly, you can tell a lot more of a story in an hour long podcast than synthesized down into a, something that they read on the screen. And because habits had also changed a bit, I think, with the rise of YouTube, I decided to create this platform that really focused on expatriation and cross-cultural living from black and brown perspectives.

[00:31:10] Amanda: Big reason behind that is a lot of the platforms I followed and listened to just didn’t have them and I really wanted the most regular people you’ve ever met talking about their most extraordinary lives, and so that for the future, black expat, they could be encouraged and inspired and hear, okay, this is a thing you can do.

[00:31:30] Amanda: And for those who are current expats, they can listen and go, oh my gosh. Yeah. Their story’s just as wild as mine. And then we’ve got people who are neither of those, who are just like nosy or like, this sounded really cool, and I love them too. And that’s really what it came around to is like, how can we consistently talk about all these different stories?

[00:31:47] Amanda: In some cases people are not expats currently, but they have been impacted by cross-cultural living. Internationally adopted, they were TCKs, they were married, cross-culturally, whatever.

[00:31:59] Louise: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. One of the ways I think about this podcast that I do, Women Who Walk, is that it’s basically in service to the stories of women who normally don’t have a voice out in the world. They’re regular women doing extraordinary things. And, and the way you describe the Global Chatter Podcast to me sounds similar. It, it’s like in service to the voice of people of color that normally would not get a chance to tell their story about moving countries, expatriation, repatriation. And then it affords the listener, um, a feeling of ‘ that, that’s my story. These are my people. I feel recognized as a result of this podcast.’

[00:32:40] Amanda: What’s really fun is what people discover about folks with stories. What’s fun for me as an interviewer are the things like when an interviewee has a reflection about their own story that maybe they haven’t thought too deeply about, but then I ask them a question and they go, oh yeah, I just realized this experience is why I’m doing this, that, or whatever. Quite frankly it is for me, it’s just fun to hear, particularly black folks who live in places you wouldn’t, like think about them living in.

[00:33:11] Louise: Like where?

[00:33:12] Amanda: Okay, so lemme say so, for example, one interesting topic I did was about the undocumented experience in the US of black individuals and how it is very nuanced, apparently, from others, when lay your race on top of it. And so I remember thinking, oh my gosh, this is a lot. Like, I’ve thought about this, obviously cause I had the person on, but like there was stuff that she was saying. I think that having Lola Akinmade Åkerström, she’s a photographer with National Geographic, and an author, and in fact, she’s about to have her, I think her second or third non-fiction or fiction book out.

[00:33:49] Amanda: I remember having her on and I was just thinking, she’s super funny because she’s of Nigerian descent, and her story is just a whirlwind of, well, I moved to the US when I was 16, she’s like super smart, right? And got into college really early. And then I think she was working GIS, geographical, something, I don’t know, information systems. But she met her husband, who’s Swedish.

[00:34:09] Louise: Ooh.

[00:34:10] Amanda: Back in the day before online dating was the thing. And then she ended up moving to Sweden because she married this Swedish man. And she’s like, at that time I decided I was gonna be a photographer. If you see her work, you’re just like, I don’t know how you do all these things. Also, you just moved to Sweden. All these interesting stories.

[00:34:30] Amanda: And, and this is the last one I will say, one of my favorite is this woman who’s an OB-GYN, and her husband is an anesthesiologist, did not travel until, I think their honeymoon because they’ve been in med school and then residency, went on a trip to Australia …

[00:34:46] Louise: Hmm.

[00:34:47] Amanda: Happened to meet another American doctor on a hike, and they were talking to her and she’s like, yeah, I live here now. Because she got a job in, it was either Australia or New Zealand. And they looked at each other and said, we could do this. Came back and figured out how to move to New Zealand. They were not in Auckland. I think they were on the other side of New Zealand. and were doctors there and we’re just like, this place is gorgeous. It’s unreal, right? It looks like it’s gorgeous.

[00:35:13] Louise: It is gorgeous.

[00:35:13] Amanda: So that’s what I mean, just like these weird stories. They did not set out to be expats. They met this random doctor. Now they live in Australia, but they’ve been living in the region ever since.

[00:35:21] Louise: And your story about the Nigerian woman photographer who then ends up in Sweden. I love that one, because a couple of episodes ago my, um, Jaia Sowden, who is mixed race, her dad is, Brazilian African, her mum’s British Italian. She ended up in Sweden and she’s, um, a photographer as well. She’s back in the UK working, but sees herself in Sweden at some point. You’ve just recounted a story that’s very similar.

[00:35:49] Amanda: I was just gonna say, Sweden, now that you said it, I was just thinking, Sweden has somehow disproportionately been featured in quite a few of mine. I say this now, cuz there’s actually an episode coming out tomorrow from Sweden.

[00:36:02] Louise: Oh, right, okay. Yeah. Okay. Well look, this has been so much fun, Amanda. Thank you so much. And so if listeners would like to learn more about you, your podcast, and of course The Black Expat, where can they find you online?

[00:36:17] Amanda: Super easy. All you need to do is start with TheBlackExpat.com and we are on all the major social media platforms, so Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, YouTube, and if you do The Black Expat on most of those, that will take you to where we are on YouTube’s a little bit different, I think it’s The Black Expat Presents but for the most part, that’s like our hub. The Global Chatter Podcast is the name of the podcast. If you go on The Black Expat, it can link you there. You can also search on all of the major podcast platforms and you will find The Global Chatter.

[00:37:00] Louise: Terrific. And I’ll link to those in the transcript and again, thank you so much, Amanda.

[00:37:06] Amanda: Thank you.

Louise: Thank you for listening today. So you don’t miss future episodes, subscribe on your favorite podcast provider or on my YouTube channel @WomenWhoWalkPodcast. Also, feel free to connect with comments on Instagram @LouiseRossWriter or Writer & Podcaster, Louise Ross on Facebook, or find me on LinkedIn. And finally, if you enjoyed this episode, spread the word and tell your friends.