EPISODE 46

April 20, 2023

Introduction

Joyce Agee is originally from the US. Currently she lives a couple of hours southeast of the Australian city of Melbourne. Her childhood was peripatetic with her family moving every couple of years. As is often the case with individuals who moved frequently as children, Joyce continued to move, relocating internationally once she’d graduated university in the mid-70s, building a successful career as a freelance photographer in London. She says, “Freelance photography is the perfect career for anyone accustomed to moving frequently. It follows the same learned pattern. We arrive, we do the job, and then we depart.” From London she moved to Australia, and then back to the US, and then back to Australia. From her website: “Moving internationally four times has tested my newcomer survival skills. Fortunately, words and images can surmount different time zones and cultural shifts.” With that in mind, this past year, Joyce released her first book, The Newcomer’s Dictionary, which she describes as the A to Z of words that explore aspects of relocation.

TRANSCRIPT

[00:00:00] Louise: Welcome to Women Who WaIk. I’m Louise Ross, writer and author of Women Who Walk the book, the inspiration for this podcast. And just as I did for the book here, I’ll be interviewing and unpacking the journeys of impressive, intrepid women who’ve made multiple international moves for work, for adventure, for love, for freedom – reminding us that women can do extraordinary things. You can find a transcript, with pictures, to each episode, and my books on my website, LouiseRoss.com.

[00:00:47] Louise: Hello, listeners. Welcome to Episode 46 of Women Who Walk.

[00:00:52] Louise: My guest today is Joyce Agee. Joyce is originally from the US, but she currently lives very close to where I grew up, a couple of hours southeast of the Australian city of Melbourne.

[00:01:06] Louise: Unlike my very settled childhood in a small rural town, Joyce’s childhood was peripatetic with her family moving every couple of years. Consequently, her mother would always introduce the family to their new community as newcomers.

[00:01:24] Louise: As is often the case with individuals who moved frequently as children, Joyce continued to move, relocating internationally once she’d graduated university in the mid-70s, building a successful career as a freelance photographer in London.

[00:01:43] Louise: On her website, she says, “Freelance photography is the perfect career for anyone accustomed to moving frequently. It follows the same learned pattern. We arrive, we do the job, and then we depart.”

[00:02:00] Louise: In 1982, she and her Australian husband relocated from London to Sydney, and then to Melbourne, where the marriage ultimately ended. In 1999 with her second Australian husband and stepdaughter, Joyce moved back to the US, to Seattle. Having lived outside her country of origin for 24 years, the challenges of repatriating were significant.

[00:02:30] Louise: In 2015, she left the US for the second time, and along with her husband moved back to Australia, her stepdaughter having already returned. Here I’ll read another marvelous line from her website: “Moving internationally four times has tested my newcomer survival skills. Fortunately, words and images can surmount different time zones and cultural shifts.”

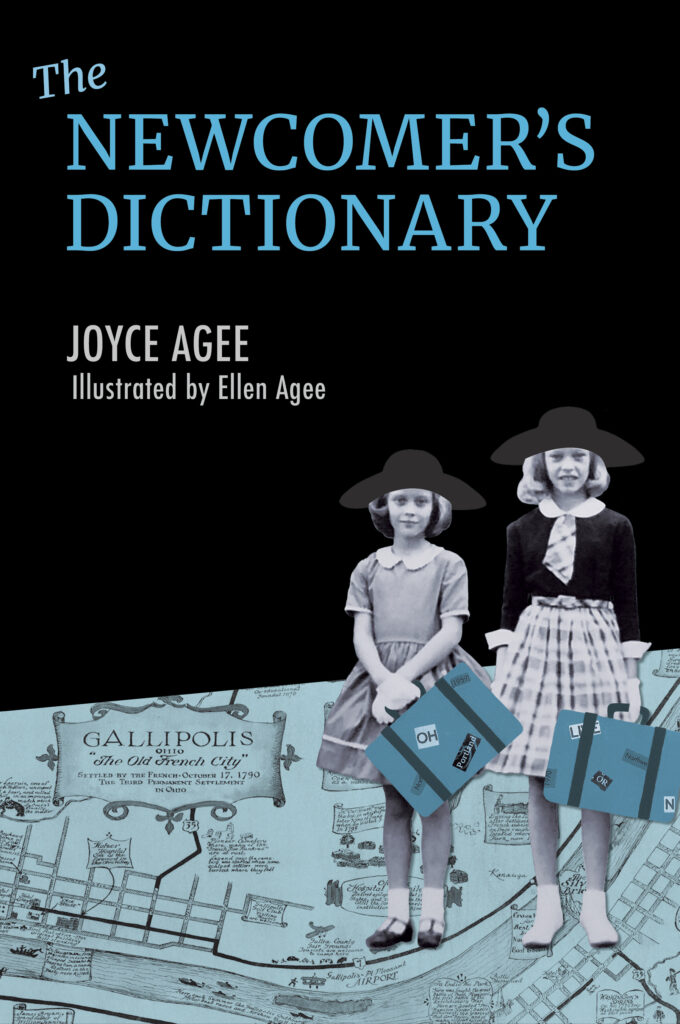

[00:03:00] Louise: With that in mind, this past year, Joyce released her first book, illustrated cleverly by her sister. The title is The Newcomer’s Dictionary, which she describes as the A to Z of words that explore aspects of relocation.

[00:03:20] Louise: One caveat listeners, there were technical issues on Joyce’s end, so the recording is a bit rustic. But hang in there as the conversation is, as with all my guests, delightfully informative.

[00:03:47] Louise: Welcome Joyce. Thanks for being a guest on Women Who Walk today. I wanted to start by having you read a quote from your website.

[00:03:56] Joyce: Louise, thanks for having us. “As a fledgling photographer, I showed my father my photographic portfolio. He responded, why be a photographer? Aren’t there enough of them already? Fortunately, I didn’t listen to him.”

[00:04:13] Joyce: And that was very important, Louise, if nothing else, you know, sometimes with adults and particularly your parents, you’re seeking approval, and I realized in that exchange and he, I actually showed him some of my photographs and he laughed at some of them, but he couldn’t get his head around having a daughter who was a photographer. I think it was just beyond his imagination.

[00:04:36] Louise: Well, you didn’t listen to him because you completed your university education in the mid-70s in Virginia, in the US, and then you moved to London where you began working as a a freelance photographer. Tell me a little about your early years, where you grew up, and then what motivated that decision to make the move to London.

[00:04:58] Joyce: When I was growing up, our father worked for a company called Reynolds Aluminium. Aluminium in America, but aluminium in other countries, and that meant that he followed the work. And so every two years we, or about two years from about the age of three onwards, we moved up and down the east coast of the United States. You can imagine the challenges children face when they’re constantly in new schools and they don’t know anyone. And this really was more of an issue than I would ever really admit to until I became an adult.

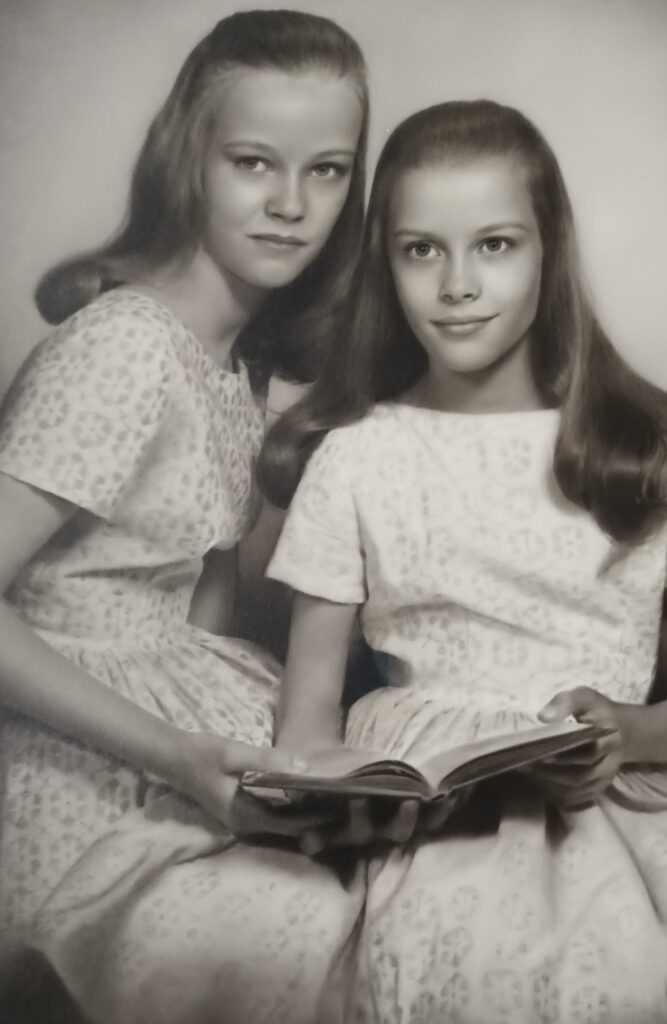

[00:05:35] Joyce: The funny thing was, so we would move from the deep south, and I know you’ve lived in the United States, the deep south to the north, and then the north back to the deep south. And if people don’t know the United States or have never lived there, they don’t realize that those are really two very different countries, in all sorts of ways, historically, language. And so what happened was my sister and I started at an early age, had to disguise ourselves and it was very important to our survival.

Joyce and her sister, Ellen, formal portrait, 1963

[00:06:03] Joyce: If you can imagine, we would move from some place like Alabama to Pennsylvania, for example. We had to lose the southern accents because there’s an association with the southern accents in the United States traditionally that you’re not very bright if you have a southern accent. So you had to lose the Southern accent otherwise you would be heckled and then you had to figure out what to wear. And there were funny things. So in the northern part of the country, you wore sneakers and in the southern part you wore like southern-kids shoes.

[00:06:39] Joyce: And there was a different vocabulary and you had to master the new vocabulary when you moved as a child as well. It was a, a good training ground, I’ll say for anyone who wants to establish a nomadic life. The basic tools are, you have to learn how to talk to anyone. You have to learn how to ask questions. You have to learn how to, in a sense, disappear so that you can belong somewhere. It was a very, on reflection, hard childhood, but valuable in many ways.

[00:07:14] Louise: Yeah, and we’re gonna get into it later in the interview, but you’ve addressed the language issue of moving and how one can be misunderstood, just by virtue of using a different vernacular of English. And you wrote a book about this, so we’re going to get there, we’re going to talk a little about it. Okay. You’ve set the scene for us. And so there was quite a bit of movement in your childhood. This choice to, to move abroad, to move to London with your photography. Do you think that that was as a result of your level of comfort with moving?

[00:07:45] Joyce: I think that what happened was I understood moving. It was something that was familiar to me. We really didn’t have any roots as a family, because you move so frequently and you have no extended family, you aren’t able to maintain friendships. It meant that I didn’t really have much to lose and so moving was not just something that I was familiar with, it was something that was easy for me and I knew how to do it well cause I’d done it so much.

[00:08:15] Joyce: When it became a possibility with the person who would be my first husband, who was Australian, um, when we moved to England, I was completely comfortable with it. I wasn’t conscious, I’ll have to admit, I didn’t really think about what I was leaving behind because this was what I knew and understood. You moved some place new. This was an international move, but it was something I recognized and was quite comfortable with.

[00:08:41] Louise: Mm-hmm. So you met your first Australian husband in the US?

[00:08:46] Joyce: The joke is Louise. I find Australians wherever I go. Where I went to university, there wasn’t another Australian for miles, but he was teaching cinema and I established a relationship with him. And actually via Australia, went to England and lived in London. So it was a romance.

[00:09:06] Louise: Mm-hmm. Well, your photography career in London really took off and your work appeared in publications such as The New Statesman, the Guardian, Timeout, and the British Journal of Photography. How did you get your big break? Because, it’s not easy, particularly these days for photographers to put together a portfolio of publications like you did.

[00:09:29] Joyce: Lack of knowledge is sometimes your best friend. When I decided that I was going to pursue a career as a photographer, I was in the best place to do it. London, at the time that I was living there, I mean, wonderful photography exhibitions. Beautiful things happening in Time Out, and just a glorious time to be a a photographer. And the other thing is, it was a good time for me and for other women; it was the burgeoning feminist movement.

[00:09:58] Joyce: And publications like Spare Rib were giving lots of opportunities for publication. You had an avenue to begin to become a professional photographer. It was not easy, but you build it up. It’s kind of an incremental thing. So I got my help from other women and I had a very important community project that I did that allowed me to have a publication and to get a reputation and to have a good portfolio.

[00:10:26] Joyce: I did a series on London cafes, and I think completely insensitive. But I would walk into any working class cafe depending on the time and ask if I could photograph. And it was much easier time. You didn’t have to get permissions and things like that. So I went into these cafes, photographed men smoking at the tables, the women preparing tea, and, and so what I did was I created a recognizable type of photograph. And through that I was able to create a portfolio which then gave me other work.

Islington High Street, London from Joyce’s photography portfolio of local community

[00:10:58] Joyce: The irony was I had just gotten my professional photographic accreditation when we left London to come to Australia, which I’d been working for. But it was an exciting career and it was a great career. I just felt so lucky to be in London at that time.

[00:11:13] Louise: You preempted my next question, which is that you had this burgeoning career in London and then made a decision to move to Australia, and I guess this was in 1982. And I just have to say that this was actually the year that I left Australia. So as I’m leaving, you are coming. And so I couldn’t help but think what was the decision to go to Australia? Because of course I was just dying to get out of Australia. So you and your husband emigrated together then, did you?

[00:11:41] Joyce: We did. He was a film critic. He is a film critic and an author, and he wanted to have an opportunity. He had been very successful writing books about early film criticism. Coming back to Australia was an opportunity for him to partake in the Australian film renaissance, which had grown while he’d been living overseas.

[00:12:01] Joyce: So he came back to take advantage of that. And I was sorry to leave London, but I was so accustomed to changing environments and changing myself that it seemed like another adventure. Coming to Australia was again, another exciting opportunity. I couldn’t have expressed it that way, but on reflection, that’s what it was.

[00:12:27] Joyce: The advantage I had was that, as you well know, there’s the cultural or was the cultural cringe here. So if you’d done anything anywhere else, there was a sense that somehow you had achieved something, it’s not the same now, but coming to Australia at that time, what I’d accomplished in London was seen with genuine interest. That gave me an opportunity to launch myself here. Again, it wasn’t easy because at the time I was here, there was always mixed reactions to me being an American. You recognize that and push through anyway.

[00:13:01] Louise: Hmm. Interesting. Good for you, because that was going to be my next question that you had success in Sydney as well, working as an official photographer for the Festival of Sydney, the Sydney Biennale and the Sydney Women’s Festival, and yes, Australians can be kind of resistant, particularly to Americans who appear to be successful or better resourced, because of this habit of cutting down the tall poppy or the successful one. So you did experience some prejudice, but you pushed through it, you say, can you a talk a bit about that.

[00:13:36] Joyce: What I did is I looked for the op, it’s almost like you look for the gaps. Certain things are not going to necessarily come your way. Being a freelancer was actually an advantage because that meant you were there temporarily, they could take advantage of your skills and then say goodbye and, and so that works fairly well in my type of position.

[00:14:00] Joyce: They wanted the skills you could bring, but they didn’t necessarily want you hanging around. What I ended up doing, for example, I tried to continue to work for the Festival of Sydney every year. So you build up a record. And if I had stayed in Sydney, I would’ve probably gotten an opportunity to do the another biennale, but by that time I was no longer living there. Again, it’s incremental.

[00:14:23] Joyce: But I think it’s the same for anybody who moves. You want people to like you and use you as a, a freelance photographer, but you also are aware that you have a specific kind of role. And it’s almost like I would compare it to a glass ceiling Louise. It’s almost like you’re hitting a cultural glass ceiling. They’ll let you go that far, to reach that point, but they won’t let you in any further. Once I knew that and understood that you work within the limitations of that, if that makes sense.

[00:14:55] Louise: Mm-hmm. It does. Gosh, I have to ask, do you think that there was something gendered about that cultural glass ceiling?

[00:15:04] Joyce: Funny you should say that. I think that one of the things that was an advantage at some point was that I was, young, and a glamorous young photographer. But that only lasts so long. My joke was that when I reached my rich middle years, if I was still gonna be a photographer, I was gonna go into theatrical photography, rather than try to be out in the world trying to convince people to let me take their photograph while they’re running or jumping or whatever they were doing.

[00:15:33] Joyce: So, I knew that there was probably a use by date. And I changed a lot of different ways to accommodate earning a living. At the time I was in Sydney doing photography, I had a specific niche, which was community photography, and I call it feminist photography. And so if I could find my landing ground for those particular areas, and it was a little tricky actually because community photography in London is a big area, it’s very easy to find your niche there, but it’s not, was not as well developed in Sydney as an idea.

[00:16:10] Joyce: The other thing, I’ll be honest with you, it was technically often a challenge because of the light. London is always under clouds, and so you have this nice filter. People look a lot better within that situation. But in Sydney the light was so bright, and I had to recalibrate literally to try to figure out how to take photographs in that kind of environment.

[00:16:31] Louise: Fascinating. And you’re quite right. Community photography is big in London. I’ve seen some hilarious exhibitions actually, at the Portrait Gallery off Trafalgar Square, of folks doing kind of community events that seem quite eccentric.

[00:16:49] Joyce: There’s this lovely sort of series of traditions that show up in community events in London. I can’t speak for it now, but when I was there it was.

[00:16:58] Louise: And that isn’t so much part of the Australian culture that, that you are aware of?

[00:17:04] Joyce: It’s a different approach. Sydney’s light and the light in Australia is like a spotlight and everything is very clear. And in London you can take murky atmospheric shots because it’s dark and, you know, gloomy, but in, in the light in Sydney was so bright that there was no kind of compromising. I do think environment does dictate sometimes the types of images that people take. You’re not going to see so many landscapes in London. You’re gonna see silhouettes of tall tower blocks and things like that and people kind of huddled. But in Sydney, not with that light. No. No way. It’s very interesting to me.

[00:17:46] Louise: Absolutely right. You gave a very visual indication of the photographic differences between London and Sydney. For me, of course, what you’re evoking as you talk about Sydney, uh, a n natural scenes. Everybody knows the Sydney Opera House and Sydney Harbor, and that’s what we think of as we think of photographs of Sydney.

[00:18:06] Joyce: As a photographer, your job is to look and so you’re to look at people, you’re to understand things visually. It’s such a wonderful way to enter into a new place. To really have the excuse to be looking everywhere and investigating everything. And that’s a hangover, of course, from my childhood.

[00:18:25] Louise: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. We’re talking about Sydney, but then you moved down to Melbourne, which is where I spent my young adult years. The culture between Sydney and Melbourne is quite different in the same way that the culture is vastly different as you go down the eastern seaboard of the US. In Australia, as you go down the eastern seaboard from far north Queensland, way down to Melbourne. Might as well be in another country. So did you have any issues adjusting from the culture of Sydney to Melbourne?

[00:18:58] Joyce: Sydney was much too exotic for me. I adjusted to it, it was before it really got overbuilt, but it was a sort of a tropical environment and very dramatic and theatrical really. If you think about, as you were saying, the Opera House and the bridge and that span over the harbor. It’s just a drama everywhere you look. I was more comfortable in Melbourne because it has more of the kind of London feel to it, the Victorian architecture, and the concentration on the art scenes. And their more of an inward-looking city. Beautiful in its own way, but, but inward. I’m afraid to tell you this joke cuz you’re Australian.

[00:19:42] Joyce: It’s joke is, if you have a good idea in Sydney, you throw a party and if you have a good idea in Melbourne, you make a publication.

[00:19:53] Louise: Is that to suggest that Melbournians are a bit more literary or intellectually snobby?

[00:19:59] Joyce: No, what it does, it kinda encapsulates the difference between the two communities. Like you’re saying, Louise, there is a big difference. But I don’t think it’s about intellectual competitions. It’s just about joy in Sydney. It’s just such a kind of lively city and, and knows it. It’s sort of a self-aware, lively city and Melbourne is a, is a more thoughtful, deliberate kind of place. You definitely have parties here, but you wouldn’t have it quite like you would with those beautiful lemon trees and those wonderful vistas in Sydney. It gets back to my point, I think environment dictates to some degree, culture.

[00:20:39] Louise: And Melbourne is more reserved. As you were explaining the difference, I’m thinking about here in Portugal, we have the European Portuguese and the Brazilian Portuguese. And the Brazilian Portuguese, love Sydney. I was in Sydney a number of years ago and I had to ask for directions and I asked this young woman who turned out to be Brazilian, and I thought, now that I’ve lived in Portugal for many years, I can see how Sydney would be really attractive to the Brazilians. It the same sort of party, subtropical vibe. So, thanks for reminding me of the differences.

[00:21:12] Joyce: And you’ll forgive me for the joke.

[00:21:14] Louise: Oh, absolutely, absolutely. I’ve lived outta Australia so many years now, things like that it’s like water off a duck’s back. Then from Melbourne, you have a young family, and you move back to the US. Back to Seattle, which to me is actually a little like the culture of Melbourne, Seattle. Talk us through your repatriation, and then your repatriation back to Melbourne in 2015.

[00:21:42] Joyce: Well, I am an Australian citizen, that lovely kind of hybrid thing, which I think is a signal of how wonderful globally we can be. What happened was I divorced, and then worked in Melbourne. And then four years later, I remarried and I helped to raise my husband’s children, who were 10 and 11 at that point. That was a huge change for me, as you can imagine, because I did not have children of my own and and so that was a steep learning curve. At that time though, I had changed my professional direction. I had adjusted and adapted, to a point where I no longer enjoyed taking photographs. I had to decide what I was going to do. So I moved into local government, cultural administration. I ran a small museum.

[00:22:31] Joyce: I had sufficient skills to make the transfer into that area and when the decision came that I wanted to try to move to the United States, I had a longing. I’ll be honest, it would’ve been a longing for a long time to have the opportunity to live and work in the United States because I had left right after college and I felt, and I dunno how else to articulate this, but I felt I needed to acknowledge and, and work for the country of my birth. I needed a sense that I had made a contribution and that I needed to also pay tribute to my grandparents who had worked so hard to establish themselves in America. It was a recognition that I had connections that I needed to complete, if you like. It became more and more important to me.

[00:23:27] Joyce: I’d never lived in Seattle nor had I any professional connections. That’s probably the common connection between all my moves. I have never been a person that has known what I’m gonna be doing when I make the move. I may work in the same field, but I will not necessarily know where I’m working.

[00:23:44] Joyce: And so we packed up our bags. We left Australia. My husband was, I think, excited about it. I, I was excited about it. My stepdaughter, who was a teenager at that point, was not so excited, but I hoped that she would have the sense of the world expanding, that you don’t necessarily have to stay in one place. And the other thing is I also knew she could probably get a better college education at less cost in the United States. It was much trickier here, to get college education. And I knew that if she had a college education, came back to Australia, she would be in a much better position. I felt.

[00:24:21] Joyce: Going back to the States was hard because I looked the part, I spoke the language, but I knew nothing. Nothing. Oddly enough, Greg being the celebrity Australian, he had a very good time. He opened his mouth and everybody went, oh, ah, ooh. Paul Hogan’s relative. So he found it easier professionally to find a, a job. My stepdaughter had a n easy time too. She had two summer jobs the first time we were there again, because she’s Australian, but they’re not supposed to understand anything. And I was supposed to understand everything.

[00:24:53] Joyce: I was supposed to understand health insurance. I was supposed to understand the prices of things, property. It took me a great deal of time to finally get a job. Because there’s very little respect, and certainly in America, for what you do someplace else. It doesn’t translate well. They don’t have a glimpse of the seriousness of what you do.

[00:25:15] Joyce: I was working in the arts and cultural field and I worked on an exhibition about Australian film stills with the National Film and Sound Archive and it was a great project because it looked at the cultural icons of this country through film. Also as a still photographer, I was very interested in seeing who was doing it and how to identify those people. Still photography is by tradition, very anonymous. I remember going to this man in this professional development firm and he looked at my resume and he tried to figure out what he was going to do with me. He looked at the exhibition, which had been toured and very successful, and he said, oh, that looks like that was a fun project. I wanted to slug him. I thought how patronizing, how dismissive, how condescending.

[00:26:02] Joyce: Eventually after a networking exercise, it was like building a family tree, that they proposed, and I followed, uh, eventually I got a job at a major event in Seattle, and that’s where I launched myself and I ended up at the University of Washington.

[00:26:18] Louise: I can identify with absolutely everything that you said. There was a period when my ex-husband, who’s American, and I separated and I went back to Australia. And I’d lived in the US, I think 10 years at that point, and this feeling that I had when I was trying to set up my life there was very similar to what you’re talking about, which is that I was supposed to know with everything, you know, I sounded like an Australian, looked like an Australian, I guess, but I couldn’t understand things. Sometimes I couldn’t understand people’s accents. They were so broad that my ear was no longer familiar with that. And I found myself saying, I’m sorry, could you repeat yourself? I didn’t understand. And that was not received well because it was perceived as me being haughty or snobby, like perhaps they should be more eloquent, which wasn’t the case. It was simply, I didn’t understand the accent.

[00:27:15] Louise: But the interesting thing was because I was coming from the US with a graduate education, and you said you felt your stepdaughter would get a better education there that she could then bring to Australia and have more opportunity there. In fact, that’s what I found, that I was offered a job quickly in Australia, in an environment where I was gonna be very well paid versus the US where I, well I was, uh, a small fish in a big sea basically, but back in Melbourne I was a big fish in a little sea. So, I hear what you’re saying and it’s very interesting to have that reflected back to me after all these years. What about your repatriation back to Australia after Seattle?

[00:27:56] Joyce: I was happy to work at the University of Washington. I was able to accomplish some things that I’m very proud of. I was able to rid myself of that sense of not being able to contribute to the country of my birth. That gave me a great deal of deeper soul satisfaction actually. We had been there for a while. Greg’s romance with America was still very vital, but he began to have some professional issues, which were not good. And I saw what was coming and I looked at where I was professionally and I knew that he would be happier being back in Australia cuz his daughter had moved back, and his family’s here. So we made the decision to move back to Australia. It was a sound decision. It was an intuitive decision, and again, we didn’t have jobs when we made this decision.

[00:28:53] Joyce: Lady luck. Let this all just unfold. Let’s see how it all works. It was hard from my perspective, because I was leaving my family behind again, but I knew that this was a better place for us to live, as we got closer and closer to retirement. You cannot turn your back on public health. There’s so many things that are so positive culturally, even though they’re not always working as well as they might. We had the illusion that coming back would be easier. But we discovered that was not the case.

[00:29:27] Joyce: Ironically, Greg, who had been a celebrity Australian for his whole time in the United States, came back and he had to get another educational credential to actually work in the same field he’d been working in the United States, which was security. Once he did that, his, his status was affirmed or confirmed. He then was able to move fairly successfully professionally.

[00:29:53] Joyce: I came back and I thought, oh, I’m bringing back a wealth of experience. I’ve worked at the university now for over a decade. I understand libraries. I understand so much more than I did when I went. After I got back here, people looked at my resume, and I had good references, and it just kind of entered the void. I couldn’t decide this time whether it was being a woman of a certain age; being an expatriate American; or who knows what many other things we could add to that list. But it took a great deal of time for me to find a position that I was prepared to take. We were very confused by all of this because we thought it would be easier than it was, and I did have some very difficult times with this readjustment in ways that I was not expecting.

[00:30:41] Louise: Well, the direction I now want to go, which we’ve alluded to is this issue of language. So you have moved to the UK from the US, to Australia, back to the US, back to Australia. All English speaking countries, though, each of these countries uses their own vernacular of the English language. And you have written a book, which I’m fascinated by, called, The Newcomer’s Dictionary. On your website you say, “it’s an A to Z of words that explore aspects of relocation.” This reentry to Australia, this second reentry was challenging. Did it have anything to do with language or did this book come out of your general overall experiences from childhood through your adulthood of dealing with differences in language?

Front cover image of Joyce’s book, The Newcomer’s Dictionary

[00:31:37] Joyce: Part of the answer is that I felt that language had not served me when I moved, regardless of what the English vernacular was. That I did not have a way of describing what it felt like to be new. I did not have the language, and I didn’t like discussing it, or even giving people an inkling of how difficult it often had been, because it made me weak or in my eyes or vulnerable, and I didn’t wanna be vulnerable. I just wanted to be able to do whatever I was needing to do in the new place I was living.

[00:32:15] Joyce: I certainly didn’t want people to feel sorry for me, and I didn’t feel sorry for myself. But when I came back to Australia, what I found was, again, I felt like I had disappeared. Everything that I had accomplished somewhere else didn’t seem to have any relevance to the life that I was beginning to live, and that was part of the significant challenge of this move. Having a whole history, having made connections and relationships and created things and it didn’t appear to be welcomed here. This made me begin to think about the way language or the lack of language handicaps you when you’re trying to describe this experience.

[00:33:05] Joyce: From that perspective, I began to think of the words that had resonated with me as a child, as an adult, and looked for the words help express some of the challenges that I think many people or newcomers face, regardless of the reasons they’re new.

[00:33:29] Joyce: When we met on Zoom with families in global transition and someone said, the difference between an expat and an immigrant is basically class, isn’t it? You’re an expat and you’re considered kind of glamorous because you can live an expatriate life. Whereas if you’re an immigrant, clearly you’re not there necessarily in the same way. And those sort of distinctions in words, I’ve begun to be fascinated by it.

[00:33:52] Joyce: And so I wrote the A to Z because there are words that are pejorative for newcomers and you don’t think about it, but they are influencing people’s perception of you. One of those would be Gypsy. Gypsy is one of those words that sounds kind of exotic. You’re a gypsy. But gypsy actually can be as a pejorative because gypsies are considered to be thieves and have a sort of dubious reputation. So if you’re called a gypsy it’s not really a compliment, and it doesn’t mean that Gypsies in themselves intrinsically are bad. It’s just when it’s referred to used as a newcomer. And the other thing that came out of that zoom meeting was the word newcomer. And one reason I used the word newcomer was because it doesn’t have anything attached to it as a word. It’s just a word. It’s just you’re new and you’re come somewhere. And so I really liked newcomers.

[00:34:46] Joyce: As I began to think about these words, and the pejorative words, there are lots: transient, hobo, homeless. I mean, there’s just a whole litany of words that are negative. When you think about for example, itinerant, and other words like that, I wanted to explore how it felt when you thought about those words and were they accurate and did they really convey a sense of what it was like to be a newcomer?

[00:35:12] Louise: Hmm. And Joyce, do you identify as an immigrant?

[00:35:17] Joyce: I think all lines blur. I’m an expat, but I’m an immigrant. Um, I’ve had a very privileged life in the way that I’ve been able to move around different countries. But I don’t identify with expat either. It doesn’t seem quite right. My joke always was I’m trans-Atlantic, that seems much more realistic to me. I’m somewhere in between all of these places. And that’s one of the challenges when you’re trying to identify what it feels like to be at home somewhere.

[00:35:44] Louise: Mm-hmm. Yes, it is. And It’s a question that I ask myself, and I keep a definition on my desktop that I, I might go ahead and read it. It says, “expat is someone living in a country other than their home country with the intention of sooner or later returning. In contrast to immigrant, intending a permanent move.”

[00:36:09] Louise: It’s maybe a little bit academic, but It certainly gives us something to think about as individuals who have intentionally left their home country to live for an extended period somewhere else, which is what you and I have done, and though of course I socialize with an expat community here, I don’t necessarily feel like I’m an expat. But yes, I go back and forth, I suppose, in order to try and understand my situation.

[00:36:37] Joyce: Well, I think that’s the thing. You are constantly in a state of balancing. Today I feel like I’m an expat. Tomorrow I feel like I’m an immigrant. Maybe I feel like I’m an exile. I mean, I think your identity changes and evolves and then goes backwards and sideways. That’s one of the challenges when you talk about having to describe this. Suddenly something will happen and you feel like you are not living in Australia or you are living in Australia. In the book, one of the things that was very moving is I used exile, because I was also looking at the words that historically have been associated with newcomers.

[00:37:18] Joyce: In that I recalled a situation where I met a taxi driver and he was Chinese and we stalled outside of the Sydney airport, because there was an accident. It was a summer day and I rolled down the window and there was heat and fumes. I was in the front though, because I don’t like sitting in the back and he and I had the time to talk and so we chatted for a while and I found out he had decided not to return to China because there had been the problem in Tiananmen Square where they had all been killed and he had decided to stay in Australia. I asked him how it had been for him to make the adjustment. He said it was very difficult for him. He had good educational qualifications in China, but they didn’t transfer to here. And so he was having to draw taxis, thinking about being a tour guide for Chinese.

[00:38:11] Joyce: I said to him things like, well, have you ever experienced thus and so? Or have you ever had a sense that you’re not welcome? And how did that feel? As we began to talk in some depth, it became clear that we had a great deal in common. My experience as a expat American living here was in some ways parallel with his experience, and he couldn’t believe that I’d had experiences that were uncomfortable and unpleasant, and I couldn’t believe that he and I shared this sort of history. It was very interesting.

[00:38:44] Louise: I just wanna reflect on the title of your book, The Newcomer’s Dictionary. When I moved to Boulder in Colorado, there was actually a volunteer organization that was staffed by local women, and it was the newcomers, club or group. Volunteers would be available to newcomers to the community to help them acclimate. Is that where the title came from, that American tradition of having newcomers clubs or groups?

[00:39:22] Joyce: My mother always referred to us as professional newcomers. That was the joke. When we would be introduced to people and they would find out that we’d lived in the north, the south, east west, she would say, ‘hi, I’m a professional newcomer.’ It was kind of a nice quick way to describe to people why we might not know anybody or why we were new. The Newcomer’s Dictionary came about because I had the most trouble trying to figure out how to combine all the different things that I was thinking about and wanting to write about. It gave me a formula that I could follow that kept me on track, if you like.

[00:39:58] Joyce: The other thing it did was it allowed me to bring in areas of interest that had been important to both my sister and myself growing up. When I thought about language and I thought about books, It was clear that we survived our childhood, being so peripatetic, was because we read and the libraries and books were our refuge. You find very often when you’re talking to people that have moved a great deal as children, arts and creative endeavors, reading and books are where they find themselves. They say, they’re saved by these things.

“Lost” an illustration by Ellen Agee from Joyce’s book, The Newcomer’s Dictionary

[00:40:39] Louise: This is a really nice place to finish up because we’ve come full circle to talk about the peripatetic childhood that you had. If listeners would like to learn more about you and your photography and your book, where can they find you online?

[00:40:54] Joyce: Instagram is joyceagee.author I do an Instagram post pretty much once a week. And I do a monthly blog on my website and that’s joyceagee.com.au

[00:41:10] Louise: The spelling is A G E E.

[00:41:13] Joyce: Yes, it’s French Huguenot. We think it got bastardized. It was probably something kind of exotic like a perfume, Agée, then when the French Huguenots came over, I think it shifted and changed.

[00:41:23] Louise: Okay. Well I will link to those sites, your social media in the transcript of this episode on my website. Thank you so much Joyce.

[00:41:32] Joyce: Thank you, Louise. I wish you the very best and I’m so honored to be part of the program you’ve been doing.

[00:41:38] Louise: Thank you for listening today. So you don’t miss future episodes, subscribe on your favorite podcast provider or on my YouTube channel @WomenWhoWalkPodcast. Also, feel free to connect with comments on Instagram @LouiseRossWriter or Writer & Podcaster, Louise Ross on Facebook, or find me on LinkedIn. And finally, if you enjoyed this episode, spread the word and tell your friends.