EPISODE 5

May 26th, 2021

Joia Lewis was born in Portugal to American missionary parents during the Salazar dictatorship. Ten years later, her family moved back to the US. After studying violin at Boston Conservatory, she continued college in Massachusetts, and at the Pushkin Institute in Moscow, Russia, graduating with degrees in Russian Language and Literature, and Soviet and East European studies. Looking for a way to continue study in both the humanities and the sciences, led to a Ph.D. In the Philosophy of Science from Indiana University. Following three decades of teaching scientific reasoning, philosophy of mind, logic and medical ethics in California and Minnesota, with a hiatus has software publications manager in Silicon Valley, she returned in 2018 to her birthplace, Portugal.

TRANSCRIPT:

[00:00:25] After studying violin at Boston Conservatory, she continued college in Massachusetts, and at the Pushkin Institute in Moscow, Russia, graduating with degrees in Russian Language and Literature, and Soviet and East European studies. In 1979, she returned from traveling throughout Europe, Africa, India, and the middle East for graduate work in the History and Philosophy of Science.

[00:00:52] Looking for a way to continue study in both the humanities and the sciences, led to a Ph.D. In the Philosophy of Science from Indiana University completed just before the birth of her daughter.

[00:01:05] Following three decades of teaching scientific reasoning, philosophy of mind, logic and medical ethics in California and Minnesota, with a hiatus has software publications manager in Silicon Valley, she has come full circle returning in 2018 to her birthplace.

[00:01:25] Joia now lives just outside Lisbon on the coast, very close to where I live, in fact. We met through the social organization IWP or international Women in Portugal, which I talk a bit about in Episode 1. Joia has served for several years on two different IWP boards as President.

[00:01:45] All this, and now in her 60s and retired, Joia has been living with a rare type of progressive multiple sclerosis for the past thirteen years. I say retired, but between her volunteer work with IWP, including an online discussion group that she facilitates in the manner of Hypatia, the Hellenistic philosopher known for her brilliant teaching and wise counsel, Joia is still active, though no longer, as she says, able to overdo it.

[00:02:17] I am thrilled to have Joia as a guest on the podcast today, as I greatly admire her tireless intellectual curiosity, which has been the driving force behind her country moves, and her courage and tenacity living with MS and the resulting physical disabilities.

Louise: Welcome Joia.

[00:00:01] Joia: Thank you very much. It’s an honor to be on this.

[00:00:05] Louise: We’re almost neighbors. You’re maybe a 15-minute walk from me. Why don’t you give listeners a sense of the neighborhood, what you enjoy about it, your favorite cafes, paint a picture for us.

[00:00:16] Joia: I’d be happy to. We would have been even closer neighbors had I gotten the original apartment I wanted, which is just down the hill from you, closer to the train station. But I am in a neighborhood that reminds me of where I grew up in Leiria, just north. Everywhere I’ve lived in the meantime, I’ve wanted to recreate a place where I can walk to my favorite coffee shop, to the post office, to the stores nearby and I’ve been able to do that here. I’m in an apartment building, my coffee shop, which I haven’t been to for so very long, I’m looking forward to breaking this isolation we’ve all had. I’m behind the casino in Estoril. It’s turned out to be a good place. There’s a lovely park in front of the Casino.

[00:01:10] Louise: Yes, that is a fabulous park. I love walking around there too. Listeners might have noticed already that you have an American accent. But in the introduction to this episode, I mentioned that you were born in Portugal, which you also just referenced, and then you spent the first 10 years of your life here. Can you tell us about that, that experience of growing up in Portugal?

[00:01:32] Joia: Yes. My parents were Evangelical missionaries in the ’50s and the early ’60s. You might not know this, but there was a Baptist seminary up in Leiria, which is about halfway between Lisbon and Porto in north central Portugal, and they were there for about 14 years. So I was born in the British hospital in Lisbon, as was my younger brother.

[00:01:58] And so I went through Portuguese kindergarten, Jardim-Escola João de Deus, which I now know is like a Montessori. It was quite a wonderful kindergarten, and through Portuguese grade school, which is called the quarta classe, and then I would have gone into the Lyceum, had we stayed. At the same time, my mother made sure that we kept up with our American grades.

[00:02:25] So she would send for a year of correspondence school from Baltimore, Maryland. I wasn’t sure where that was, but that’s where we got the box of second grade, third grade, fourth grade that I completed. And my older brother was four years ahead of me, so I got to listen to all the grades up through eighth grade.

[00:02:46] Then at the same time we had Alliance Francaise. We had a Parisian teacher, who came to teach people in Portugal the correct Parisian pronunciation of French. So it was quite jarring to end up in the United States, outside of Boston. All of a sudden I had to stay in one room all day long and they called me by my English name, Jewel, instead of my Portuguese named Joia, which was very odd. So there was a lot to get used to at that time.

[00:03:19] Louise: You integrated into American culture when you were 10 and that’s after spending your formative years in Europe, and it sounds like you would have been speaking three languages, English, Portuguese, and French, going back into a conventional American school system. Plus, you had grown up here under the dictatorship, so enormous cultural adjustments that you had to make. Can you talk a little about that?

[00:03:49] Joia: It was a huge adjustment. And I must say, I may never have quite adjusted in the 50-plus years I did spend in the United States with traveling in between. But it was difficult. It was difficult on religious grounds. My parents had left in the early ’50s and they were coming back into the United States in the middle of the ’60s. Whereas I had friends who were very much the cultural middle class, working class here in Portugal, that class in the United States was all of a sudden outside the Evangelical group. And I had not been aware of the religious divisions before. That was quite different. The education was quite different. We had been brought up with a lot of music. We did piano lessons in Portugal. In fact, my brother and I used to say, ‘you know, we’re great-grand pupils or Franz Liszt,’ because our Portuguese piano teacher was a student of Vianna da Motta, who was one of the great Portuguese classical pianists and he was a student of Franz Liszt. We were very proud of that.

[00:05:01] But all of the things that are important in Europe for a child to be good at something, all of a sudden in the United States, it was just the opposite. You had to hide that you knew something. All of a sudden having visited the Louvre and the Vatican and the British Museum made me odd, instead of being something positive. As a professor, I would always tell my students, especially my international students, I did terribly on the SATs and it didn’t stop me from getting a Ph.D. in Philosophy of Science.

[00:05:37] So I always encouraged them. You have your intelligence. This is not the same as your intellect, because an intellect is, is arbitrary. It depends what facts you’ve picked up in one culture or another. What books you’ve read. What education you’ve had. That was very important to me to get that message across because I did not do well in the cultural, the American slang, I was a foreigner, but kind of an invisible foreigner. I didn’t have an accent in English any more than in Portuguese, but I, I just simply didn’t know what everyone else seemed to know.

[00:06:16] Louise: And one of the things that you touched on is the rich cultural experience that you had growing up in Portugal and music was very much a part of your, uh, young life. And then you went on to study music.

[00:06:31] Joia: Yes. I was very fortunate to have parents who were in the educated Evangelical culture. Even though they were in a minority in Portugal, bringing a Protestant religion to a very Catholic country, as most of Southern Europe is, they were also very excited to be able to travel during the summers, and as I mentioned to take us to all the great museums and all the big sites.

[00:07:00] Germany where my grandmother’s cousin lived, she was the matriarch of a farm in Blankenheim, and we would go and visit our cousins there. And so there were things available to us growing up in Europe that simply would not have been the case in the Midwest where my parents were from.

[00:07:19] Musically I did continue. My brother went on with the piano, I went on with the violin, which made my mother happy. She was also a violinist. When my father finished his graduate work at Brandeis, he went to teach Old Testament at a Christian college in St. Paul, Minnesota, so I went to junior high and high school there. At that time, I got into the St. Paul Youth Orchestra, which was a wonderful organization, and I was able to play all the great symphonies. We even made a record, which was so much fun in high school.

[00:07:56] I later went to Boston conservatory. And I’m so glad that I did. Because I found out that I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life playing in an orchestra, which my teacher wanted me to do. I was just beginning the Brahms violin concerto when I started to read Russian literature of all things. And it touched a chord in me that this was the next step. I often feel very strongly that what I’m doing at the moment will lead me to the next phase of my life. And I was certainly correct with that. I switched to U. Mass to the program in Slavics and then went to Moscow to continue studying Russian language.

[00:08:40] Louise: That’s what’s most curious to me about your story is that you then left the US and you went to the Soviet Union. In fact, it was Pushkin Institute in Moscow, graduating with degrees in Russian Language and Literature and Soviet and Eastern European studies. What do you think drew you to such a difficult language and another country that somewhat mirrored the dictatorship of Portugal. Do you think that there was some similarity between your experience growing up in Portugal and your pull to study in Russia?

[00:09:17] Joia: I didn’t at the time, but I certainly do now. I see many similarities. Portugal is off on the West of Europe and the Slavic world is off on the East of Europe. And in some ways there are similarities, but at the time, what drew me to the language, I think, because I had studied language and I knew that poetry and literature and history is open in a new way once you can read in that language. And since I had already done that, I was open to learning a new language. I had tried to learn a bit of German. German reminded me of my grandmother not being happy with me. She would kind of yell German proverbs and things when she was disappointed in my behavior. And I didn’t have a good association with the language. But that didn’t keep me from reading the literature, at least in translation.

[00:10:15] Once I discovered Russian literature, I was absolutely enthralled and it was 19th century Russian literature. So I must say, even though I did go to the Soviet Union in 1978, I spent five months there, four months in Moscow and two weeks each at a different time, traveling in Kiev, Novgorod, Leningrad, which is back to being St. Petersburg, Vilnius in Lithuania, it was quite exciting to be there and to visit the small towns around Moscow, with the beautiful old churches from the 12th century.

[00:10:53] I was looking for the 19th century. I was looking for Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky’s Russia and was fascinated with everything about that. But I had been taking courses about the Soviet Union. And when I walked into the Pushkin Institute in Moscow, I had the same feeling that I was in the stucco walls of the Baptist seminary up in Leiria. I put that away on the back shelf, but it’s come back to haunt me quite a bit. In the healthcare system as well, the public healthcare system in Moscow, when I’ve been in older clinics and older hospitals in Portugal, I’ll have an equivalent fear that I’m in a the place where I may not be getting the best help and I may not be able to explain to anyone what I need. So I have to be careful with these types of memories. They may or may not be literary or actual, but they certainly bring a lot of color into my life and into my writing.

[00:11:55] Louise: This might be a place to talk a little about your health journey. I did mention it in your biography that you’re living with MS, did that begin to appear or did you have symptoms at the point of which you were in Russia?

[00:12:08] Joia: I have a rare form of MS that doesn’t show up until your 50s and 60s. It’s called primary progressive MS. I had never heard of it. I knew a lot about the other kind of MS that you get in your 20s and 30s and you deal with very various attacks and remissions throughout life. My cousin has this type. So I was very surprised. I date the beginning of my awareness of symptoms to the year 2007. It took another three years for an actual diagnosis. It was very unclear why I was having trouble lifting my left foot off the ground. Then I was diagnosed with MS, but it wasn’t clear what kind in 2009.

[00:12:59] Because I was teaching in St. Paul college at the time, I had access to Mayo Clinic in Rochester, and I finally went there in 2012 and after six months of a team of doctors and researchers investigating the disease it was bittersweet news. But they did confirm that it was primary progressive MS. I’m fortunate that it has been stable. It is now 12 years. Even my neurologist thought it was a good idea to move back to Portugal. Now with the stability, I don’t have pain, but I do have weakness on my left side. That is challenging. It’s taught me a lot, to live in the world as a disabled person. It slows things down and maybe in a good way for me. It’s certainly, slowed me down. I have more time to reflect and do the things I’d like to accomplish still in my life.

[00:13:56] Louise: I want us to come back to that, but let’s go back to your extensive travels throughout Europe and Africa and India and the Middle East, was that just part of your post-Russian experience?

[00:14:08] Joia: Yes, the beginning of these travels are very specific to new year’s Eve in Frankfurt, Germany in 1977. I was on my way to the Soviet Union with 25 exchange students. What happened after that trip is that I had gotten to know the tour leader and he said that he had been put into the DP camps, the displaced person’s camps, with his Polish family after World War II and then ended up in the United States. I was the first person he met who said, okay, let’s go! Let’s go see the DP camps. And that started a year of traveling together, which was absolutely wonderful. When I think about what I’ve done later in my life with formal degrees, I always throw in the traveling.

[00:14:59] We were able to go south to Greece, Egypt all the way down to Kenya, and then over to Pakistan, India, Nepal, and then back through the Middle East. We had a round trip ticket from Luxembourg back in the days when you could fly Icelandic Air for $300. That’s what we did. And this year of traveling was wonderful for me. We would try to spend about a month in each country to get to know what was going on. We tried to travel as much as we could, like local people. The second, third class in these old British trains across the continent. Then we would try to have one good meal a day. So we’d hit the fancy restaurants for that meal. And the rest of the time we had our Bunsen burner and we would boil water, whatever we needed to do. It was an education that I couldn’t have had in any other way.

[00:15:54] Louise: At what point through this journey do you decide to head back to the US?

[00:15:59] Joia: When I moved in with the tour leader, who ended up being my first husband, I remember walking into his study, seeing all the books, that I would buy as a Slavic scholar in the next 20 years and I thought, oh my goodness, I can’t do this. It’s not that I wasn’t interested any longer, but what I kept returning to was the fact that my favorite Russian writers like Dostoyevsky knew the science of the times, knew the history, knew the psychology, knew the politics. Dostoyevsky had been an engineer before he became a writer and there was something in the ideas that I wanted to pursue.

[00:16:43] He would often write about non-Euclidean geometry of all things. I had no idea what that was, but I thought, somehow we’re moving from the linear and the three dimensional to something new. And I need to know what that is. In pursuing these ideas, in a way I invented my next field of the history and philosophy of science. I wanted to study the humanities, and also study the sciences. What would give us our world view? My husband at the time got a job at Indiana University for a year. The plan was we’ll make some money and go to China. Well, we got as far as San Francisco and realized we didn’t have enough money, but we ended up staying there. And I enrolled in the history and philosophy of science department. There are only two in the United States in Pittsburgh and in Bloomington, Indiana.

[00:17:41] I was fascinated with this subject. I started taking night classes and then the professors told me I should enroll. And I said, I’ll go get a master’s in a science in physics or biology, then I’ll be back. And they said, ‘Oh no, we’ll take you right now.’ And the next year they put me on Ph.D. track. I didn’t even write a master’s thesis. I just kept taking courses, very happily educating myself. I thought, this is something that would put me in a place where I could then write my novels.

[00:18:15] That’s really what I was thinking at the time. I had no plans to become a professor. I was ready to keep traveling and writing and I thought, I’ll write better novels if I have this education behind me. I’m still at that place now as a retired professor.

[00:18:32] Louise: Wow, you’ve got degrees in music, language, and then philosophy of science. Do you feel that there’s some interconnection between these various studies that you have done?

[00:18:46] Joia: Absolutely and everything I did, particularly in retrospect, when we can always make good sense of things, one thing led to another and it has been my curiosity, a drive to understand. I also must say that the older I get the less I know. I’m with Socrates there. I know that I do not know, as the horizons get pushed out further. The mastery of one area has really shrunk for me as I’ve continued to learn about other things.

[00:19:18] I think the best compliment I ever received was from one of my professors when I finished the graduate work and went on to teach, she wrote that ‘Joia has breadth as well as depth.’ It meant something to me, that I did learn my own field, and what I did research in was the Vienna Circle Physicists, who became philosophers between the two World Wars. And they were fascinating to me because they wanted to redo German philosophy. They were not interested in the H’s: Hegel and Heidegger. They would make fun of German philosophy and say, after Einstein, we need to apply science to philosophy, otherwise it’s just silly armchair thinking and it won’t get us anywhere. But that project of applying one’s worldview to one’s philosophy, I found it delightful and I continued to want to do that and to work in that spirit.

[00:20:22] But I haven’t stopped loving music. I continued to play my violin whenever I could. I couldn’t really practice the way you need to. So I started to sing at one point, after my daughter was born. I realized I could deposit her as a baby in the church nursery, and I could go off and sing. And I very heretically would choose a choir with paid singers and ex-opera singers and section leaders. And I got to sing Mozart Requiem. I enjoyed that a lot.

[00:20:55] My daughter’s father, who became my second husband, was a jazz musician. And, our first date, he put me on the guest list for the Video Saloon in Bloomington, where all the good jazz groups played. And because I love Baroque music, and because I was aware that Bach and the other Baroque composers wouldn’t write every single note, they would write the chord. It was quite like a jazz chart where the soloists would come in and improvise around that particular series of chords. And the more I heard and the more I listened to the jazz soloists, the good players were just astonishing to me.

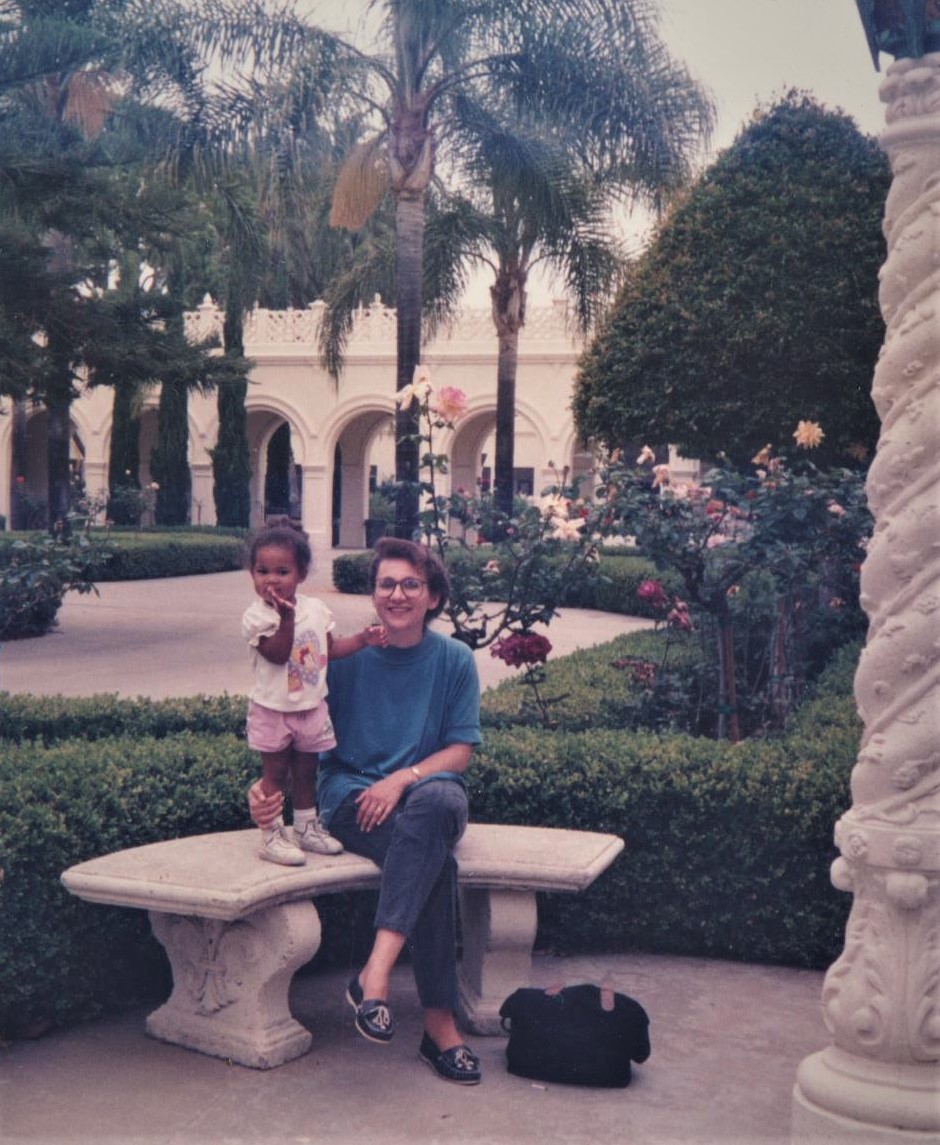

Joia & her daughter outside her teaching office at the University of San Diego 1991

[00:21:36] I could not make that transition. And I tried with the jazz bass at one point, to go from classical to jazz and I couldn’t let go of the visual. I need to see the music and then I memorize it. I transfer it to the violin neck, and then I’ve got it. And you can’t do that with jazz. It’s like a language and you’re drawing from that language and you’re expressing it in the moment. What I could do with words, I was not able to do with notes, but I certainly saw the correlation in those two.

[00:22:10] Louise: Once again, this very, very rich and eclectic background that you had, uh, led you into teaching. Many years teaching, but then you had a stint in the world of technology out in California. Is that right?

[00:22:25] Joia: That’s correct. I call it my seven-year hiatus in Silicon Valley. At that time, my daughter was a teenager in California and a professor’s salary isn’t a whole lot anywhere in the United States, but particularly not in California. And even though I had an interdisciplinary degree, my salary was that of a humanities professor, which can be a half of what a science professor’s salary is. So, I became technical publications manager for a software and network management company.

[00:23:00] That was very interesting to me. At one point I asked to move from the marketing sales into the engineering department, because I said, what I’m doing is basically what I did as a logic professor. The computer scientists, they have the same courses I did basically, in learning, detecting a language, the logic language.

[00:23:23] I was able to communicate with them, as the person who wrote the software manuals or I then hired people to write them, I was able to see that what they were doing in improving software very often made things more complicated for the user. I was like the liaison between the technical engineers and the people who had actually used the software. When I returned to teaching, in the early part of the 21st century, the ‘aughts’ as they call them , I had a good knowledge of the technical background and I was able to move into online teaching and hybrid courses, which I might not have been able to do from a blackboard to the PowerPoint, to all the online platforms.

[00:24:12] Louise: That’s a great indication of how your inclination to go in a particular direction, then opens a door for you to go somewhere else, which has been the way that your life has unfolded. And then perhaps that’s one of the reasons you returned to Portugal to follow an inclination to return to your origins. Can you tell us a little about that?

[00:24:39] Joia: I always did want to come back and live in Portugal at some point. I started to write a book called Notes From a Portuguese Exile. If I live long enough, I’ll write that, because it does feel in a way that there’s a part of me in my adopted culture in Portugal that I needed to investigate. My mother passed away in 2017, she was 93, and at that point, my apartment building had been bought by some luxury department developers. They increased the rent astronomically and I moved out and then thought, now it’s time for the next chapter of my life. I am disabled. I am retired. Where do I go from here? So I began to look in the other direction and think about whether I could live in Portugal.

[00:25:31] My daughter is now in her thirties, and I thought, now is probably the time to go while my health is relatively stable. And so I did, and it has been an interesting journey. A lot has happened. I feel very good about my decision to come back. It has now been over three years. I’m still in touch with my childhood friends in Leiria. But what has been a great joy to me has been to meet other expats, particularly the women I’ve met through IWP, which I knew nothing about until I came here, and Louise you are one of those people.

[00:26:12] Louise: I am indeed. That’s how we met. And a couple of times you’ve referenced yourself as disabled and yet, you’re still so active. I know you have good days and bad days, but you’ve been incredibly participatory in IWP and the various roles that you’ve had on the boards. And of course now you’re facilitating this wonderful online group. Tell us a little about that group. I also mentioned that in the introduction, it’s a wonderful concept.

[00:26:40] Joia: Yes. The salon concept is quite old. What came through the United States is the idea of the Socrates cafe, which was started by a journalist in New Jersey. And those have grown and they’re all over the globe now. People who get together, choose a topic and discuss it in a coffee shop, in a nursing home, in a school, all over the place. And I had participated in some of those in California. They’re not academic. I would always tell my students, we’re all philosophers. We’re all trying to understand what we’re doing here. What things mean. If we can trust our eyes, etcetera.

[00:27:22] We had some salons previously in IWP, during the pandemic, we could not meet in person, so I was willing to start one online. Instead of Socrates, we chose a woman philosopher, Hypatia from Alexandria, a wonderful mathematician and philosopher and teacher. And so we’re calling it the Hypatia cafe and we have not yet met in person, but I’m looking forward to that. For the time being, we pick a topic and we have no trouble going into detail discussing what a certain topic, uh, like truth or introvert-extrovert, or, uh, technology, what these things have done to our sense of who we are, of ourselves. The cultural differences we’ve all lived in and this particular community of people who’ve lived all over the world and have dealt with life in different languages, different approaches, it’s quite amazing. I’m enjoying it a lot and as I always did as a teacher, I learn from my students. I learn from my friends and that’s basically how I keep going. I know there’s more for me to do understand.

[00:28:39] Louise: I’m nodding my head and smiling, because I love this group that you facilitate. One of the classes I took in my undergraduate degree was philosophy. And I really loved our breakout small tutorials, which are a little like the Hypatia cafe, because it was just maybe half a dozen of us and we’d sit around and it was great, juicy discussion. And you’re such a source of wisdom and a wonderful facilitator, that that group is a fabulous forum to come together and dig deep on some of these topics.

[00:29:13] So as we finish up, Joia, you’re living comfortably in Portugal, you’re managing your health. Are there any plans? Is that book part of your future plan?

[00:29:24] Joia: I have several books in mind. I continue to write essays and poetry, but I do have some other things in mind. I always say if I live long enough, I’ll get to all these things and may even do some more professional writing as well. I’m back in touch with graduate students, people who are all over the world. In India, in Barcelona, in Paris and Venice and there’s a lot of richness in following people’s lives through time.

[00:29:54] What has impressed me the most since I’ve been back here is the familiarity, the comfort of coming back to a culture that was so much a part of my youth. Also, it has another side. It’s been difficult to have a child’s understanding of the culture. I did not develop the adult coping mechanisms in Portuguese. So in a way, I think it’s easier to be an expat when you don’t hear the language in the same way. And what I’m aware of is that in Portuguese, I will often hear the emotion, the intensity. That’s louder for me, even than the meaning of the words. Whereas in English we speak in more of a monotone and it’s the definition of the words that will come through.

[00:30:46] Louise: You have a blog don’t you where you explore some of these ideas.

[00:30:51] Joia: Yes. I started a blog, I called it Joia’s Rhapsody’s in D minor, I suppose because I played the Wieniawski Concerto in D minor. I played a number of things in D minor, but also the D is always for Dostoyevsky. He’s the Big D in my life, the writer, the thinker that’s behind a lot of my ideas. So, what I’ve done is I’ve called each of the essays a ‘Rhaps’, R H A P S, and they’re raw material that I would like to use in a philosophical memoir of sorts.

[00:31:29] Also, because I am sensitive to what was happening here in the culture as a dictatorship in the 20th century in Portugal, and with my work in the Soviet Union, I’ve become very interested in the idea of how trauma exists under tyranny. That is another area that I would like to write in kind of a micro-macro view of when people are considered inferior, when they are seen as not deserving of life in the way that the people in power are deserving of life, and that can be women, that can be people of color, that can be a refugee, a torture victim, whatever happens to a person individually can also be seen as happening to an entire culture and identity, class. And so I, I’ve become more interested in exploring those kinds of ideas as I get older. Much of my writing is drifting in that direction and I would like it to congeal into a book-length work at some point.

[00:32:38] Louise: A very powerful note to end on. Thank you for sharing that Joia, I look forward to reading that book. And then listeners can also find you on LinkedIn. Is that right?

[00:32:50] Joia: Yes. I am also on LinkedIn. Yes.

[00:32:53] Louise: Under Joia Lewis.

[00:32:55] Joia: Uh, yes.

[00:32:56] Louise: Well, thank you so much for being available this morning, this has just been a delight to unpack your journey and find out more about your personal story.

[00:33:06] Joia: Thank you, Louise. This has been wonderful. It reminds me of who I am. I need that after the isolation of this past year.

[00:33:15] Louise: Yeah, me too. That’s why I love these conversations.

[00:33:19] Joia: Yes, absolutely.

Louise: Thank you for listening today. And if you would like to read a transcript of this episode, you can find it in the show notes on my website LouiseRoss.com. And if you enjoyed this episode, please rate and review Women Who Walk on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser.