EPISODE 30

July 7, 2022

In this interview, my guest, Tanya Crossman, talks about her own experiences as a TCK relocating from Australia, her country of origin, to the US as a teen, and then living in China as a young adult and over the last 10 or more years living and working between China, the US, and Australia. From her position as a cross-cultural consultant and TCK specialist, she talks through the current, and ever-evolving definition of a Third Culture Kid (TCK). Tanya is also the author of Misunderstood: The impact of Growing up Overseas in the 21st Century, which weaves together interviews and surveys with 300-plus TCKs to provide a window into their world. And her most recent publication, a co-authored white paper titled, Adverse Childhood Experiences in Globally Mobile Third Culture Kids is an eye-opening and important piece of research.

TRANSCRIPT

[00:00:00] Louise: Welcome to Women Who WaIk. I’m Louise Ross, writer and author of Women Who Walk the book, the inspiration for this podcast. And just as I did for the book here, I’ll be interviewing and unpacking the journeys of impressive, intrepid women who’ve made multiple international moves for work, for adventure, for love, for freedom – reminding us that women can do extraordinary things. You can find a transcript, with pictures, to each episode, and my books on my website, LouiseRoss.com.

[00:00:47] Louise: Hello listeners, welcome to Episode 30 of Women Who Walk. My guest today is Tanya Crossman.

[00:00:55] Louise: Tanya is my fifth guest in a series of interviews that I’ve been doing with young women, who I met through the online organization, Families in Global Transition. I first met Tanya in 2021 when FIGT put out a call for volunteers to help staff their very first virtual conference. Prior to the pandemic, their annual conference was an in-person event and in fact, I’d been looking forward to attending their 2020 conference, which was to be held in Bangkok, but then due to COVID, it was canceled.

[00:01:35] Louise: Tanya, who in my mind is a bit of a technical whizz, was coordinating the backend details of the platform FIGT used to host its first virtual conference. And she was also teaching the volunteers such as myself, how to use it.

[00:01:54] Louise: As I got to know, Tanya, I discovered that outside of her volunteer work with FIGT, she’s the Director of Research and Education Services at TCK Training in Canberra, Australia. ( TCK is the acronym for Third Culture Kids.) Third Culture Kids She’s also an intercultural trainer, consultant, writer, and advocate, specializing in support for TCKs, their parents, carers, educators, school administrators, and associated organizations.

[00:02:32] Louise: In our interview, she talks through the current definition of a TCK and she also talks about her own experiences as a TCK relocating from Australia, her passport country, to the US as a teen, and then living in China as a young adult and over the last 10 or so years living and working between China, the US, and Australia.

[00:02:57] Louise: She is the author of Misunderstood: The impact of Growing up Overseas in the 21st Century, which weaves together interviews and surveys with 300-plus TCKs to provide a window into their world.

[00:03:14] Louise: And her most recent publication, a co-authored white paper titled, Adverse Childhood Experiences in Globally Mobile Third Culture Kids is an eye-opening and important piece of research that I’d recommend any listeners identifying as an adult TCK, or who are in a role caring for TCK children, should take the time to read.

[00:03:41] Louise: Links to Tanya’s book and her white paper are available in the transcript to this episode.

[00:04:00] Louise: Welcome Tanya, thanks for being a guest on Women Who Walk. You’re Australian, and you’re actually in Australia at the moment, and I’m wondering if you can give us a brief overview of the last couple of years, to the extent that you’re comfortable, because I realize that the pandemic was a very difficult time for you. And then maybe a brief overview of exactly where you are.

[00:04:23] Tanya: Exactly where I am is often an interesting question, especially in the context of the pandemic. So I was living in Beijing in China. For us, the pandemic actually started in January of 2020 so a few months before most of the rest of the world. We started on lockdowns and restrictions in mid-to-late January. And by March things had started to open up in Beijing. It was a bit easier and I had a business trip scheduled to Thailand and Cambodia, and we talked about it, my husband and I, and I decided to go.

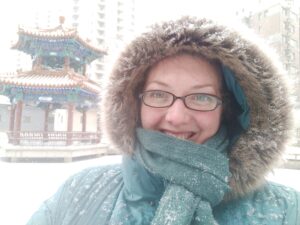

Tanya during lockdown in Beijing, 2020

Tanya during lockdown in Beijing, 2020

[00:04:59] Tanya: While I was in Cambodia, everything changed. China closed its border quite suddenly, with very little warning, and Australian government sent out an email to all of us overseas saying, if you’re in a safe place and you have access to healthcare and shelter and everything stay where you are. If not, and you’re planning to come back to Australia, do it now.

[00:05:22] Tanya: I got on a plane, after several canceled flights, I might add, I got on a plane and I came to Canberra in Australia to my parent’s house where I am right now, two-and-a-half-years later, because China never reopened the border. It’s still closed to someone like me who had a valid work permit, had a home, my husband, all my stuff, my work waiting for me. I was never able to go back. So we decided we would leave and settle elsewhere, but we don’t share a passport country. My husband’s American, I’m Australian, and we don’t have residency in each other’s countries.

[00:05:57] Tanya: So for the last two-and-a-bit years, he’s been living in the US; I’ve been living in Australia and we’ve worked on paperwork for me to get to him there, which is still in process. And it’ll probably be at least another year before I can join him there. That’s the short version, but actually right now he’s visiting me, which is, is very nice.

Tanya enjoying the winter sun in Canberra, Australia, 2021

[00:06:20] Louise: He managed to get out to Australia because the borders opened up there early this year. Didn’t they?

[00:06:25] Tanya: Yes. Yes. Australia not just opened it up to other people to come in, they also changed some of the entry requirements, so it was much easier. When I went to visit him for Christmas a year-and-a-half ago, and I had three months with him, when I came back, Australia changed the rules right as I was about to come back. I was quite lucky. I was on one of the last flights before they changed. I had to pay $3,000 to sit in quarantine for two weeks, but I didn’t have to have the PCR test within, 24 or 40, however many days. At the time, where we live in the States, it was not possible for me to get a PCR test that quickly. I would’ve had to go a couple of hours south and stayed overnight at the airport or even two nights or overnight at the airport where there was a testing clinic that would do that for me. That actually wasn’t possible where we were living.

[00:07:18] Tanya: It was, it’s all very complicated and there’s a lot of additional stresses to these travel restrictions that people don’t often understand, that not everyone has access to all kinds of healthcare. As a non-citizen, I didn’t have access to go to a doc, I couldn’t even pay to get a doctor’s appointment to get a PCR test because you couldn’t do that on a first appointment. And on a first appointment, you had to schedule so much time in advance. Like there just, there was no way to do it.

[00:07:43] Louise: The other thing is it’s an incredibly dramatic story because you’re, you basically shut out of the country in which you were living for? How many years was it? It was 10 years. Wasn’t it?

[00:07:53] Tanya: The first time was over 10 years, 10-and-a-half years. I moved there when I was 21, for a year and stayed for 10-and-a-half, as you do. I came back to Australia for three years to study, and then I moved back and I’d been there two-and-a-half years when I got stuck.

[00:08:10] Louise: I see.

[00:08:11] Tanya: But my husband, he had to leave the only place that’s been home, he’s been living in Beijing since he was 14′ ish.

[00:08:19] Louise: Oh, okay. Mm-hmm and he had to leave.

[00:08:21] Tanya: I had the work visa. So his only option was to go to the police every 30 days and ask for permission to stay another 30 days. My work visa was about to run out. My new work visa was sitting there waiting to be picked up, but I had to pick it up in person, and he couldn’t get it.

[00:08:34] Louise: Well, this is a story you’ll take with you for the rest of your life, really? Cause it is so dramatic. I wanna talk a little bit more about China and I noticed on your Facebook page that you studied Mandarin at Beijing Language and Culture University and also at the Australia National University. So why Mandarin and was it your studies that initially took you to Beijing?

[00:08:55] Tanya: It was my studies that took me to China originally, but the real answer to why Chinese starts when I’m 11. In Grade 7, you had to pick a language to study. My school offered Japanese, German, and Chinese. Japanese was a language my sisters were doing in their primary school. German was the language my mother had done all through high school to quite an advanced level. I picked the language that no one at home could correct me in. And it was in that simple, it was my stubbornness. That stubborn streak is what started me out. And then every year or two, some coincidence would happen that would keep me there.

[00:09:33] Tanya: My family moved to the US where they didn’t offer any Asian languages at school. I went to a huge school that had 14 languages, including ancient Greek and Latin, but they didn’t have any Asian languages on offer. So my dad’s company paid for tutors and I got along really, really well with my Chinese tutor and that got me re-interested in the language and invested in it.

[00:09:55] Louise: Mm-hmm.

[00:09:56] Tanya: And then I continued it.

[00:09:57] Louise: This is while you’re living in the US?

[00:09:59] Tanya: Yeah. I had this tutor who came to my house once a week.

[00:10:03] Louise: Where were you?

[00:10:03] Tanya: We were in Connecticut, just outside New York City.

[00:10:06] Louise: Anybody else around you studying Mandarin?

[00:10:09] Tanya: When I went back to Australia after being in the US, yes, but not in the US. It was just me.

[00:10:15] Louise: I wondered if it was because there’s encouragement in Australia to study Asian languages because of our geographic proximity to Asia and the business with Asia that had encouraged you to, to take it up.

[00:10:28] Tanya: That’s a huge reason why those languages are accessible to me. But as a, as a young child, I didn’t care about that at all. And even when I was older that, wasn’t what influenced me. It was the fact that this language was the one I was interested in. If that language hadn’t been accessible to me at 11, I’m sure it would’ve been something else.

[00:10:45] Tanya: When my sisters and I were going through high school in the ’90s, most of the schools in our area in Canberra would have three language offerings. It’d be one European and one Asian and Japanese. Almost every school offered Japanese back then. These days, Chinese is getting more common in primary schools because you’ve got Chinese organizations subsidizing that teaching. So I think it’s becoming more common now than it was back then.

[00:11:12] Louise: It certainly wasn’t available when I was a kid. It was only Latin languages.

[00:11:16] Tanya: Yeah.

[00:11:16] Louise: So that’s, that’s an interesting reflection on the evolution of, uh, Australia’s immigration policies too, I think.

[00:11:24] Tanya: I think so.

[00:11:25] Louise: While living in Beijing, I understand that you end up working with third culture kids.

[00:11:29] Tanya: Yes.

[00:11:29] Louise: Or TCKs, and in particular, children of expats and then you did this briefly in Cambodia?

[00:11:37] Tanya: Yeah.

[00:11:38] Louise: Yeah. And while there, you’re also working on a book about TCKs. I’m guessing your work with expat kids informed your writing and your book. So can you tell us first, what was the work that you were doing and, and then what is your book about?

[00:11:53] Tanya: It definitely changed over time. It started out with a friend saying, ‘Hey, I’m working with this group of kids, you should come and volunteer and be a mentor.’ I’m like, okay, fine.

[00:12:09] Louise: This is in China?

[00:12:10] Tanya: Yeah. In Beijing. Was a very mixed group. It was an international church youth group, but it was business kids, it was diplomat kids, it was, uh, some military kids, not as many in, in China, the military kids, but there were some; it was teacher’s kids, whose parents were teaching in the international schools, and some of them in the local schools and universities; there were missionary kids. Huge variety of backgrounds from every corner of the world.

[00:12:39] Tanya: I started helping out with running conferences and camps for these kids a couple times a year. We’d often have 150-to-250 people at these retreats and 95 passport countries sometimes. I mean, it could get that ridiculous. I learnt the Chinese names for all the countries so I could help the hotel staff fill out the paperwork. I knew which countries had handwritten passports. It was fascinating. But my introduction to this community was very globalized, very multi-ethnic, very cross-sector and that’s really informed my understanding of the third-culture-kid world. The expatriate world was very much a mixed group, very different kinds of families, very different kinds of backgrounds.

[00:13:24] Tanya: And so I started out just spending time with young people. Mentoring and supporting and being a big sister to, to kids who were long way away from their extended families. Over time, it became clear that I was much more interested in that than I was in my ‘work,’ work. After a while, so I’d probably been doing it maybe five years, I switched over to working more full-time in that place, in that area, in third culture kids, a mixture of part-time paid work and some of my own consulting. Then I wrote the book and I moved more into international education consulting where schools would have me come in and help with the work they were doing with their students.

[00:14:05] Louise: Is that what the book is about?

[00:14:07] Tanya: When I wrote the book, it was around the time that there was a resurgence in literature for third culture kids. Before that there had been one big book: Third Culture Kids Growing up Among Worlds, and there were a few books giving some advice to parents or to educators. There were a few books that were memoir, but there was very little, if anything, that was giving a broad perspective of how TCKs felt about their lives that was modern to the internet age, that was speaking from the kids’ perspective and not them as a subject. And I felt there was this gap in the market, that there was a story that wasn’t being told. And I had spent nearly 10 years by this point, meeting with, mentoring, talking to hundreds and hundreds of these kids, and I wanted their stories to be better represented.

[00:14:58] Tanya: But a large part of it also is I’d been spending a lot more time with parents. And so many of the parents I was talking to felt a lot of guilt, a lot of anxiety, a lot of stress around we don’t know what the trajectory is for our kids, because the way we were raised, the way we were parented, the society we grew up in is so different to what our kids are experiencing, so we don’t know what happens next. Being able to say to them, look, this is the trajectory of kids who are like yours and what they have been through and what this has looked like for them, both the positive and the negative, here’s how you can help. Here’s how you can support. Here are questions to ask to better understand your kids and their point of view. So I wrote it on those two levels for parents to better understand and support their kids. And for the third culture, young people themselves to know they aren’t alone, that other people have been through the same things.

[00:15:50] Tanya: A lot of it is quotes from interviews. I did nearly 300 interviews. And so there’s quotes from young people saying, this is what I went through. And often the comments I get back from people is, I didn’t know there were other people who felt the same way I do. That’s a huge part of the responses I get, that sense of recognition. It’s not just me. I’m not the only one. It doesn’t matter who you are, that sense when you find someone who shares your experience is so powerful.

[00:16:16] Louise: It is, it, it really normalizes and connects people so that it opens the door for a, for a conversation that’s very supportive. Before we move on to the next question, which is a bit more about some of the research work that you’ve done, maybe just give us a, a current definition of a TCK because it’s evolving and it’s, it’s a moving target.

[00:16:38] Tanya: One of the biggest difficulties in the moving target is, is a third culture kid, necessarily someone who’s moving between different countries or just moving between different cultures. Depending on which definition you pull, some will say specifically that a third culture kid is someone who lives outside their passport country, usually because of their parents work or study, that’s why they leave their passport country, live in a different passport country, or even sometimes they’re born outside their passport country with the intent of moving back. So it’s a different experience to an immigrant family, in that they know they’re temporary. They live in this constant state of temporary. And this is where it is very much part of the experience of expatriate families and of temporary migrant families, where you choose to identify your experience, when there’s a temporary nature to that movement. But there is also that sense of the cross-cultural nature, so someone who’s between cultures.

[00:17:35] Tanya: I particularly enjoy

[00:17:37] Tanya: Ruth Van Reken’s cross-cultural kid model, where she talks about different ways we engage with different cultures, and then she reserves the traditional TCK definition for someone who moves between countries or a domestic TCK experiencing different cultures within a country. My niece and nephew, who recently moved from Alice Springs to Canberra, that’s quite a big difference in the landscape, they miss the red color, the makeup of their school population, there’s a cultural difference there. Even just going country to city. There’s a cultural difference there.

[00:18:10] Louise: Domestic TCK, I didn’t even know that that was a potential population!

[00:18:15] Tanya: Some people will put all cross-cultural experiences under the third culture kid label. I’m very much of a self-selecting group. If the third culture kid label is something that is helpful to you, go for it. Call yourself a third culture kid. I’m not gonna gatekeep. But there are people who want to make different boxes for different people. And so you’re gonna hear different definitions depending who you’re talking to.

[00:18:41] Tanya: A cross-cultural kid, whether they’re a third culture kid or not is engaging with more than one cultural system as a child. So they are learning more than one way to do things. Mobility is also part of it so there’s grief with mobility, in addition to the cross-cultural nature. Transience and travel can be part of that in addition to the cross-cultural piece. But it’s different for every kid.

[00:19:05] Tanya: A huge chunk of my book is just pulling apart all these different kinds of experiences, because you can be a third culture kid, who lives in one country their whole life, it’s just not their passport country. And you could be a third culture kid who moves every year or every two years, or you could be a TCK who goes to local school in the local language and culture, but you speak a different language at home and you’re expected to go to a different country for university. There there’s so many different varieties. Some TCK end up getting citizenship in the country that they’ve lived in, as a foreigner. Some TCKs grow up in countries where they can never become citizens because that pathway isn’t open to them. So there’s a lot of different kinds of experiences within that one label.

[00:19:52] Louise: Gosh. Yes. You really are an expert in this. I’m just going, have you repeat Ruth’s name. You mentioned it before, but it got muffled.

[00:19:59] Tanya: Ruth Van Reken. Ruth Van Reken and David Pollock wrote the original, Third Culture Kids Growing up Among Worlds. The third edition was co-authored with David’s son, Michael Pollock, who I actually work with now. In the third edition, it includes Ruth’s cross-cultural kid model, which is a diagram trying to explain the fact that there is this umbrella under cross-cultural kids. And one of those is the third culture kid. And under that umbrella, you’ve got the diplomat kids and the military kids and the mission kids. There’s lots of different umbrella terms for lots of different types of experiences, but all are different kinds of cross-cultural experience.

[00:20:39] Louise: So then you’ve recently co-authored and released a research paper on adverse childhood experiences in global-mobile, third culture kids. Can you maybe give a summary of the findings documented in this paper?

[00:20:54] Tanya: Absolutely. Last year, I collaborated with TCK Training on a survey of developmental trauma in globally-mobile, third culture kids. So third culture kids who have moved between countries or have been caught between countries. We looked at ACE scores, that’s Adverse Childhood Experience scores. You’re looking at 10 different types of childhood trauma. This is a type of research that’s been done for decades. It started in the 1990s. There are hundreds, thousands of studies worldwide looking at the impact of ACE scores on long-term development. And so from all of these decades and hundreds of studies, we know that if you have a score of four or higher, you have a higher risk of negative health outcomes. So behavioral, psychological, physical health. That includes things such as greater difficulty overcoming addiction, higher rates of mental illness, depression, suicidal ideation, higher rates of cancer and autoimmune conditions, especially, like asthma.

[00:22:00] Tanya: We have lots of research that shows that. What we wanted to do in this research is look specifically at the globally-mobile TCK population and see if adverse childhood experiences were on an equal level, higher, lower than what we would see in a typical population; ask about additional developmental trauma that is not counted in those ACE scores, and then also to be able to break them up by different sectors to see if that made a difference. If the amount of times you moved or what kind of sending organization you were with or what kind of school you attended made a difference to your risk factors?

[00:22:39] Tanya: We only have a sample of about 2000 people and it was not random sample.

[00:22:45] Louise: That seems, that seems large!

[00:22:47] Tanya: Out of millions of people worldwide. And it’s a non-random sample. So people have chosen to take the survey, but still our numbers were quite significant. In the biggest survey that’s ever been done on ACE scores, it was the CDCs Kaiser Study in the US, 17,000 Americans, 12.5% of Americans had these high risk, ACE scores. In our study, it was 20.5%. Significantly higher.

[00:23:12] Louise: Mm-hmm.

[00:23:13] Tanya: By way of example, in other countries it’s lower often than the US scores. The Philippines did a study where they had 9% with the high risk scores. Immediately, just looking at that, you can see that while a lot of people think of these globally mobile, international globe-trotter kids as quite privileged, they’re not gonna be depressed, they’re not gonna have PTSD, they’re not gonna have these problems, we can see that they’re at risk or at least a larger percentage of them are at risk.

[00:23:43] Tanya: And so what we hope to do with those finding is to be able to get people to pay attention to global mobility in childhood as a potential risk factor, because what we’ve seen anecdotally, in many cases, kids have gone looking for help and support and said, ‘I’m struggling with my mental health’ and practitioners have said, but there’s nothing wrong. They can’t see childhood mobility as a potential source of long-term trauma that could be leading to certain symptoms.

[00:24:15] Tanya: What we’re hoping to do is, is to have this as a platform to lead to more research, to lead to more awareness, that mobility can be a problem. When you looked just at kids who had significant mobility, extreme mobility, so moving house, moving location, 10 or more times, or moving house, 15 or more times, the rate of ACEs goes through the roof. The high risk ACEs goes up to 32 and 33%. One third of the extreme-mobility kids had these high risk ACE factors, which is huge.

[00:24:51] Louise: It is. Does it seem to relate to the fact that children need a firm, secure foundation and mobility doesn’t really give them that. That being transient causes a great deal of stress. And actually when we began our offline conversation, we were talking about cortisol levels. Does it have something to do with the increase in a cortisol response to the stress of, of movement and lack of, uh, secure home base?

[00:25:24] Tanya: The work we do in preventive care looks a lot at those stress hormones, because we don’t want kids to be in that place. ACE scores don’t take that into account at all. ACE scores are just looking at the environment they’re in, especially their household environment. So ACE scores are much more likely to reflect the parent stress levels. What we see in the ACE factors, huge numbers of these TCKs saying when they were children, they felt emotionally neglected or emotionally abused, or their parents were suffering from depression or mental illness. And that’s what we would expect because of the parent stress levels in transition. I actually think the ACE scores are showing more about the parent’s stress. I think a lot of what our numbers are saying is that sending organizations need to take up the responsibility to care better for the people they’re sending, the families that they’re sending.

[00:26:14] Louise: Mm-hmm.

[00:26:14] Tanya: And giving them the resources, they need to be healthy and stable in a holistic sense.

[00:26:20] Louise: That’s profound. So it has more to do with the impact of the parent’s mental health on the children.

[00:26:27] Tanya: The other sort of research that we cite is into positive childhood experiences. So there’s been a whole field of research into PCEs, Positive Childhood Experiences, and the hope framework, which is all about how do we counteract the risk of the high ACE scores. And when you look at those, this is where I think we see that impact of transience, because a lot of those PCEs are about emotional connections in community. Some of it’s about connection with your parents. Some of it’s about connection with school friends. Some of it’s about connection with broader community and with non-parent adults. And I think those things are harder to maintain while you are moving frequently, it takes much more deliberate, consistent engagement and effort to make that happen when you are in transit.

[00:27:16] Tanya: A big effort for us coming out of this research is to focus more and more on equipping, not just parents, but communities to surround each other with these PCEs, to be those non-parent adults, to be these community spaces, to support childhood friendships so that kids have these PCEs forming, even if they are in international and transient communities.

[00:27:45] Louise: I also noticed on your Facebook page that you completed a Master’s of Divinity at the Australian College of Divinity in 2017. Was your decision to study theology influenced by your work with third culture kids?

[00:28:01] Tanya: Yeah, it was. Part of it was knowing that I needed a challenge, and a break, I’d been working nonstop in that field for a while and I needed to do something different. I wanted to spend some time in Australia with my aging grandparents. And so there was some considerations around that and the timing of it. But part of it honestly, was that I had been working in these very cross sector groups, but a lot of the theology that was presented was quite white and Western and less cross-cultural, less culturally contextualized.

[00:28:38] Tanya: The Australian college of theology, accredits multiple colleges across Australia, I chose one that focuses specifically on cross-cultural work. I was able to take classes in inter-cultural teaching, and a few other things that were helpful to me and have continued to be helpful actually in my international education work. And I ended up doing a thesis on the theology of citizenship in heaven, for third culture kids. How do third culture kids look at this particular piece of Christian theology? I found it really interesting, but a lot of ways it was for me to go and do something for myself. And yet it has really benefited my work in ways I hadn’t expected, honestly.

[00:29:20] Louise: I just assumed it would, I thought a degree in theology would give you the tools to be with these kids who often times are really struggling.

[00:29:30] Tanya: I remember a particular class and it was a theology class where the lecturer said , okay, If you are comfortable, you don’t understand it properly. No one should be comfortable with a black and white answer. This is someone who is top of his field, lectures internationally saying you should not be comfortable with a clear answer. And that was extremely validating to hear, because I look for wanting to understand the pieces that don’t fit nicely and neatly and evenly. I wanna hear the stories that don’t fit in the box. I want to include the voices that aren’t being included. And so to be in an academic environment where that was valued, was really positive for me.

[00:30:20] Louise: You mentioned representing the voices and, and voices leads into my next question, which is a slightly tangential to some of the TCK stuff we’ve been talking about. I saw a blog post on your website about Australia day, which is Australia’s national holiday. And I was hoping that you might read an excerpt that I identified as rather interesting.

[00:30:42] Tanya: “Sometimes I am mimicked with a cute accent and strange vocabulary that make me a novelty. It comes close to the tokenism, many minority groups experience. Sometimes my identity is an Australian gets erased. Sometimes I’m told I don’t have an Australian accent. Sometimes that’s true, as my accent does shift towards American when I’ve been overseas long enough.”

[00:31:04] Louise: Thank you. I was curious about this because I thought that you might be able to address accents as a form of identity.

[00:31:13] Tanya: This is something I’ve done a lot of thinking about. And again recently my accents gone through more changes. I’ve now been in Australia for five of the last seven years. And this is the most Australian I’ve sounded, since, nearly 20 years, probably. Even though my husband’s American, even though, none of my coworkers are Australian. I went through such a long process of so much of my life being identified by my accent. As a teenager in the US, I went to a school with 2,400 students and as soon as I opened my mouth, everyone knew who I was. My accent identified me. And then in China, as a young adult, in a environment where English was often spoken in international groups, but the Australian accent certainly wasn’t a prominent accent. In Cambodia, the Australian accent was much more normal. There was much more Commonwealth kind of community there, but in Beijing it was a very American expat community in the English-speaking community.

[00:32:14] Tanya: Constantly having to shift who I was to fit in. It was either be your Australian self and stand out or shift to make life easier. There are times at which I would like insist on not having to change who I was for other people. And there were times at which I’m like, it is just not worth it. But I felt that tension of changing myself for other people, and it took a long time to work out that those changes were also under my control, like I had chosen this life. That being international could be my identity as well, that the international accent and the fluidity of my accent was a mark of who I was in the life I’d chosen.

[00:32:55] Tanya: While I chose an international life, TCKs don’t. Plus they’re often dealing with a lot of expectation from family members to have a certain kind of accent. That can be really difficult and even painful for some TCKs, wrestling with the accent issues.

[00:33:14] Louise: Indeed. I attended an online presentation on that topic. I think she is Korean and she was talking about losing some of her language, some of her accent such that she then couldn’t fully communicate with her parents.

[00:33:29] Tanya: I remember many times mid-conversation with my American husband in China, getting stuck halfway through a sentence, cuz my brain had brought out three words: an Australian word, an American word and a Chinese word and couldn’t decide which one to say. And even though he would understand all three of those words, I got stuck trying to pick the right one and there doesn’t have to be a right one. Any of them are okay. I can just enjoy it; the multiple cultures and accents is part of my story and part of my journey.

[00:33:58] Louise: That’s right. Well, speaking of your American husband, there’s another paragraph in that same blog post that you read from previously, and I’m wondering if you’d read this particular paragraph.

[00:34:09] Tanya: “Being married to a non-Australian is also affecting my sense of identity and connection to country. Being Australian, how that culture shaped who I am, how deeply connected I feel to the geography I grew up in, how that identity as an expatriate has impacted me, is a big part of me and my life. And it’s a part my husband doesn’t share. He’s visited Australia twice for a total of three weeks, but my culture is foreign to him. Our life together is not Australian. Australia will never be our home in the way that it was my home. My relationship to my own country has changed and it leaves me feeling a little uncertain, like part of the foundation has shifted underneath me and I don’t know where it will settle.”

[00:34:52] Louise: Thank you. I’m guessing there are many listeners in bi-cultural marriages, so I’m wondering if you have any words of wisdom for those listeners who identify with what you wrote.

[00:35:03] Tanya: That was a couple years ago, after Josh had only been twice to Australia. He’s currently on his fourth visit to Australia. So until this current visit, he’d been in Australia three times for a total of five or six weeks. By the time he’s finished this visit, he’ll have been here twice as long in one go than in all his other visits combined.

[00:35:22] Tanya: After my first year of marriage, I came to Australia on my own. I had an event to go to, I had two new nephews I wanted to meet and we just couldn’t afford for both of us to come back both in time and money. We decided that I would go on my own for two weeks, and I did. And while here I realized, oh, I have this sense of relief; there’s this whole part of me that’s coming out and I’m like, that’s not okay. I realized what I’d done is I had taken into my marriage that ‘hold back pieces of yourself’ to get along in international society, I’d brought into my home and into my marriage. Like that’s not okay. So I had to work out what does it look like to be Australian in my home with someone who’s not Australian? Who, all these things that I’ve said there, who doesn’t share these things.

[00:36:08] Tanya: And because my husband’s a TCK, he also doesn’t share having a country that is home, that is elsewhere. He’d lived in Hong Kong and then mainland China since he was 10, and in Beijing specifically since he was 14, high school. There was so much about my experience he didn’t have. So we did things like we picked some Australian TV shows to watch together, and I started being more careful about using Australian vocabulary at home. I started making Pavlova, an Australian type of dessert, at Chinese New Year. When I do Christmas with his family, we have Christmas Pavlova, just try to bring in a few things that make a life that is a mixture of our countries not, I have my Australianism over on the side – it’s part of the heart of our life. And that has been really important, but it had to be an active process. It wasn’t gonna happen automatically. It’s been really, really lovely, working that through sharing those pieces of culture has been really, really nice.

Tanya in the US, carving her first Halloween pumpkin, 2020

[00:37:07] Louise: It sounds like you’ve learned how to blend cultures really well.

[00:37:11] Tanya: I mean, not perfectly, but just knowing that there’s something to do, I think helps knowing that it it’s a work that you have to work at was a big step.

[00:37:22] Louise: Well, thank you so much for your time today, Tanya, and if listeners would like to connect with you, read your articles, your research paper, or your book, where can they find you online?

[00:37:32] Tanya: You could find me at tanyacrossman.com. I’m also on most social media. I’m @TanyaTCK on Twitter, that’s where I’m the most active. I’m also @misunderstoodTCK on Instagram and Facebook, Misunderstood being the name of my book. And the white paper is at TCKtraining.com/research

[00:37:52] Louise: Terrific. Okay. So I will link to those in the transcript to this episode. And again, thank you so much.

[00:38:00] Louise: Thank you for listening today. So you don’t miss future episodes, subscribe on your favorite podcast provider or on my YouTube channel Women Who Walk Podcast. Also, feel free to connect with comments on Instagram @LouiseRossWriter or Writer & Podcaster, Louise Ross on Facebook, or find me on LinkedIn. And finally, if you enjoyed this episode, spread the word and tell your friends.